Born 6 October 1923Gökçedam, Osmaniye, Turkey

Died 28 February 2015 (aged 91)İstanbul, Turkey

Occupation Novelist

Period 1943–2002

Notable works

Ağıtlar ("Ballads"; debut)

İnce Memed ("Memed, My Hawk")

Teneke ("The Drumming-Out")

Ince Memed II ("They Burn the Thistles")

Notable awards

Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger

1979

Prix mondial Cino Del Duca

1982

Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur de France

1984

Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

1997

Grand Officier de la Légion d'Honneur de France

2011

Spouses

Thilda Serrero (m. 1952–2001)

Ayşe Semiha Baban (m. 2002–2015)

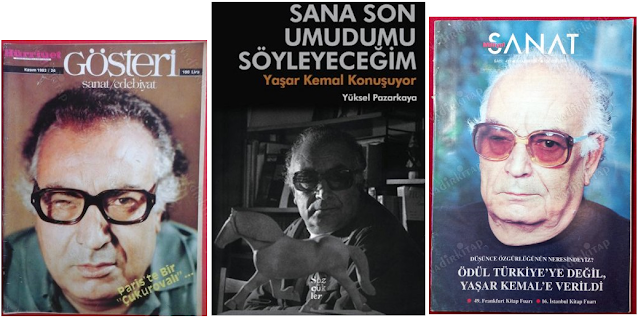

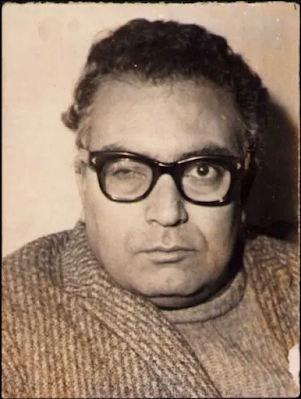

Yaşar Kemal, (born Kemal Sadık Gökçeli[1] 1923) is a Turkish writer of Kurdish origin. He is one of Turkey's leading writers.[2][3] He has long been a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, on the strength of Memed, My Hawk.[4]

As an outspoken intellectual, he does not hesitate to speak on sensitive issues.[5]His activism resulted in a twenty-month suspended jail sentence, on charges of advocating separatism.[6]

Life

Kemal, was born in Hemite (now Gökçedam), a hamlet in the province of Osmaniyein southern Turkey. His parents were from Van, who came into Çukurova during theFirst World War. Kemal had a difficult childhood because he lost his right eye due to a knife accident, when his father was slaughtering a sheep on Eid al-Adha, and had to witness as his father was stabbed to death by his adoptive son Yusuf while praying in a mosque when he was five years old.[1] This traumatic experience left Kemal with a speech impediment, which lasted until he was twelve years old. At nine he started school in a neighboring village and continued his formal education in Kadirli, Osmaniye Province.[1]

Kemal was a locally noted bard before he started school, but was unappreciated by his widowed mother until he composed an elegy on the death of one of her eight brothers, all bandits.[7] However, he forgot it and became interested in writing as a means to record his work when he questioned an itinerant peddler, who was doing his accounts. Ultimately, his village paid his way to university in Istanbul.[7]

He worked for a while for rich farmers, guarding their river water against other farmers' unauthorized irrigation. However, instead he taught the poor farmers how to steal the water undetected, by taking it at night.[7]

Later he worked as a letter-writer, then as a journalist, and finally as a novelist. He said that the Turkish police took his first two novels.[7]

When Yaşar Kemal was visiting Akdamar Island in 1951, he saw the island's Holy Cross Church being destroyed. Using his contacts to the public, he helped stop destruction of the site. However, the church remained in a neglected state until 2005, when restoration by the Turkish government began.[8]

Marriages

In 1952, Yaşar Kemal married Thilda Serrero,[9] a member of a prominent Sephardi Jewish family in Istanbul. Her grandfather, Jak Mandil Pasha, was the chief physician of the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[10] She translated 17 of her husband’s works into the English language.[11] Thilda died on January 17, 2001 (aged 78) from pulmonary complications at a hospital in Istanbul, and was laid to rest atZincirlikuyu Cemetery.[11] Thilda is survived by her hushand, her son Raşit and a grandchild.[11]

Yaşar Kemal remarried on August 1, 2002 with Ayşe Semiha Baban, a lecturer forpublic relations at Bilgi University in Istanbul. She was

educated at the American University of Beirut, Bosphorus University and Harvard University.[12]

Works

| “ | I don't write about issues, I don't write for an audience, I don't even write for myself. I just write. | ” |

—Interview with The Guardian.[13] | ||

He published his first book Ağıtlar ("Ballads") in 1943, which was a compilation of folkloric themes. This book brings to light many long forgotten rhymes and ballads and Kemal had started to collect these ballads at the age of 16.[1] His first storiesBebek ("The Baby"), Dükkancı ("The Shopkeeper"),Memet ile Memet ("Memet and Memet") were published in 1950. He had written his first story Pis Hikaye ("The Dirty Story") in 1944, while he was serving in the military, in Kayseri. Then he published his book of short stories Sarı Sıcak ("Yellow Heat") in 1952. The initial point of his works was the toil of the people of the Çukurova plains and he based the themes of his writings on the lives and sufferings of these people. Yaşar Kemal has used the legends and stories of Anatolia extensively as the basis of his works.[1]

He received international acclaim with the publication of Memed, My Hawk(Turkish: İnce Memed) in 1955. In İnce Memed, Yaşar Kemal criticizes the fabric of the society through a legendary hero, a protagonist, who flees to the mountains as a result of the oppression of the Aghas. One of the most famous living writers in Turkey, Kemal is noted for his command of the language and lyrical description of bucolic Turkish life. He has been awarded 19 literary prizes so far and nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973.

His 1955 novel Teneke was adapted into a theatrical play, which was staged for almost one year in Gothenburg, Sweden, in the country where he lived for about two years in the late 1970s.[14] Italian composer Fabio Vacchi adapted the same novel with the original title into an opera of three acts, which premiered at the Teatro alla Scala in Milano, Italy in 2007.

Kemal lays claim to having recreated Turkish as a literary language, by bringing in the vernacular, following Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's sterilization of Turkish by removing Persian and Arabic elements.[7]

Awards and honors

- 1997 Stig Dagerman Prize

- 1997 Peace Prize of the German Book Trade

- 2013 Bjørnson Prize (Norway)

Bibliography

Stories

- Sarı Sıcak, ("Yellow Heat") (1952)

Novels

- İnce Memed (Memed, My Hawk) (1955)

- Teneke (The Drumming-Out) (1955)

- Orta Direk (The Wind from the Plain) (1960)

- Yer Demir Gök Bakır (Iron Earth, Copper Sky) (1963)

- Ölmez Otu (The Undying Grass) (1968)

- Ince Memed II (They Burn the Thistles) (1969)

- Akçasazın Ağaları/Demirciler Çarşısı Cinayeti (The Agas of Akchasaz Trilogy/Murder in the Ironsmiths Market) (1974)

- Akçasazın Ağaları/Yusufcuk Yusuf (The Agas of Akchasaz Trilogy/Yusuf, Little Yusuf) (1975)

- Yılanı Öldürseler (To Crush the Serpent) (1976)

- Al Gözüm Seyreyle Salih (The Saga of a Seagull) (1976)

- Allahın Askerleri (God’s Soldiers) (1978)

- Kuşlar da Gitti (The Birds Have Also Gone: Long Stories) (1978)

- Deniz Küstü (The Sea-Crossed Fisherman) (1978)

- Hüyükteki Nar Ağacı (The Pomegranate on the Knoll) (1982)

- Yağmurcuk Kuşu/Kimsecik I (Kimsecik I - Little Nobody I) (1980)

- Kale Kapısı/Kimsecik II (Kimsecik II - Little Nobody II)(1985)

- Kanın Sesi/Kimsecik III (Kimsecik III - Little Nobody III) (1991)

- Fırat Suyu Kan Akıyor Baksana (Look, the Euphrates is Flowing with Blood) (1997)

- Karıncanın Su İçtiği (Ant Drinking Water) (2002)

- Tanyeri Horozları (The Cocks of Dawn) (2002)

Epic Novels

- Üç Anadolu Efsanesi (Three Anatolian Legends) (1967)

- Ağrıdağı Efsanesi (The Legend of Mount Ararat) (1970) - the base of the operaAğrı Dağı Efsanesi 1971

- Binboğalar Efsanesi (The Legend of the Thousand Bulls) (1971)

- Çakırcalı Efe* (The Life Stories of the Famous Bandit Çakircali) (1972)

Reportages

- Yanan Ormanlarda 50 Gün (Fifty Days in the Burning Forests) (1955)

- Çukurova Yana Yana (While Çukurova Burns) (1955)

- Peribacaları (The Fairy Chimneys) (1957)

- Bu Diyar Baştan Başa (Collected reportages) (1971)

- Bir Bulut Kaynıyor (Collected reportages) (1974)

Experimental Works

- Ağıtlar (Ballads) (1943)

- Taş Çatlasa (At Most) (1961)

- Baldaki Tuz (The Salt in the Honey) (1959-74 newspaper articles)

- Gökyüzü Mavi Kaldı (The Sky remained Blue) (collection of folk literature in collaboration with S. Eyüboğlu)

- Ağacın Çürüğü (The Rotting Tree) (Articles and Speeches) (1980)

- Yayımlanmamış 10 Ağıt (10 Unpublished Ballads) (1985)

- Sarı Defterdekiler (Contents of the Yellow Notebook) (Collected Folkloric works) (1997)

- Ustadır Arı (The Expert Bee) (1995)

- Zulmün Artsın (Increase Your Oppression) (1995)

Children's Books

- Filler Sultanı ile Kırmızı Sakallı Topal Karınca (The Sultan of the Elephants and the Red-Bearded Lame Ant) (1977)

filmography

Beyaz Mendil (The White Handkerchief), directed by Lütfü Akad, 1955

Namus Düşmanı (Dishonourable), directed by Ziya Metin, 1957

Alageyik (The Fallow Deer), directed by Atıf Yılmaz, 1959

Karacaoğlan’ın Sevdası (The love of Karadjaoglan), directed by Atıf Yılmaz, 1959

Ölüm Tarlası (The Field of Death), directed by Atıf Yılmaz, 1966

Ağrı Dağı Efsanesi (The Legend of Mount Ararat), directed by Memduh Ün, 1974

Yılanı Öldürseler (To Crush the Serpent), directed by Türkân Şoray, 1981

İnce Memed (Memed My Hawk), directed by Peter Ustinov, 1984

Yer Demir Gök Bakır (Iron Earth, Copper Sky), by Zülfü Livaneli, 1987

Eser (18)

•Menekşe Koyu Menekşe Koyu Sinema Filmi 1991

•Mutsuzlar Mutsuzlar Sinema Filmi 1990

•Yer Demir Gök Bakır Yer Demir Gök Bakır Sinema Filmi 1987

•Memed My Hawk Memed My Hawk Sinema Filmi 1984

•Yılanı Öldürseler Yılanı Öldürseler Sinema Filmi 1981

•Ağrı Dağı Efsanesi Ağrı Dağı Efsanesi Sinema Filmi 1975

•Bebek Bebek Sinema Filmi 1973

•Ala Geyik Ala Geyik Sinema Filmi 1969

•Urfa İstanbul Urfa İstanbul Sinema Filmi 1968

•Beşikteki Miras Beşikteki Miras Sinema Filmi 1968

•Ölüm Tarlası Ölüm Tarlası Sinema Filmi 1966

•Murat'ın Türküsü Murat'ın Türküsü Sinema Filmi 1965

•Karacaoğlan'ın Kara Sevdası Karacaoğlan'ın Kara Sevdası Sinema Filmi 1959

•Ala Geyik Ala Geyik Sinema Filmi 1959

•Dertli Irmak Dertli Irmak Sinema Filmi 1958

•Namus Düşmanı Namus Düşmanı Sinema Filmi 1957

•Kara Çalı Kara Çalı Sinema Filmi 1956

•Beyaz Mendil Beyaz Mendil Sinema Filmi 1955

Awards and distinctions

Literature prizes

"Seven Days in the World's Largest Farm" reportage series, Journalist's Association Prize, 1955[46]

Varlik Prize for Ince Memed ("Memed, My Hawk"), 1956[46]

Ilhan Iskender Award for the play adapted from his book of the same name, Teneke ("The Drumming-Out"), 1966[46]

The International Nancy Theatre Festival – First Prize for Uzun Dere ("Long Brook"), 1966 -Theater adaptation from roman Iron Earth, Copper Sky.[47]

Madarli Novel Award for Demirciler Çarşısı ("Murder in the Ironsmith's Market"), 1974[46]

Choix du Syndicat des Critiques Littéraires pour le meilleur roman etranger (Eté/Automne 1977) pour Terre de Fer, Ciel de Cuivre ("Yer Demir, Gök Bakır")[39]

Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger 1978 pour L'Herbe qui ne meurt pas (Ölmez Otu); Paris, Janvier 1979.[48]

Prix mondial Cino Del Duca decerné pour contributions a l'humanisme moderne; Paris, Octobre 1982.[39]

The Sedat Simavi Foundation Award for Literature; Istanbul, Turkey, 1985.[48]

Premi Internacional Catalunya. Catalonia (Spain), 1996[48]

Lillian Hellman/Dashiell Hammett Award for Courage in Response to Repression, Human Rights Watch, USA, 1996.[48]

Stig Dagerman Prize (Swedish: Stig Dagermanpriset), Sweden, 1997.[49]

Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels, Frankfurt, Germany, 1997.[50]

International Nonino Prize for his collected works, Italy, 1997[48]

Bordeaux, Prix Ecureuit de Littérature Etrangère, 1998[46]

Z. Homer Poetry Award, 2003

Savanos Prize (Thessaloniki-Greece), 2003

Turkish Publishers' Association Lifetime Achievement Award, 2003

Presidential Cultural and Artistic Grand Prize, 2008[51]

The Bjørnson Prize (Norwegian: Bjørnsonprisen), Norway, 2013.[52]

Decorations

Commandeur de la Légion d'Honneur de France; Paris, 1984.

Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres, Paris, 1989.[53]

Grand Officier de la Légion d'Honneur de France; Paris, 2011.[54]

Krikor Naregatsi Medal of Armenia, 2013.[55]

Honorary Doctorates

Doctor Honoris Causa, Strasbourg University, France, 1991.[53]

Doctor Honoris Causa, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey, 1992.[48]

Honorary Doctorate, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey, 2002[56]

Honorary Doctorate, Çukurova University, Adana, Turkey, 2009 [57]

Honorary Doctorate, Boğaziçi University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2009[58]

Honorary Doctorate, Bilgi University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014[59]

References

Obituary – New York Times

Yaşar Kemal – YKY

Ertan, Nazlan (6 March 1997). "French pay tribute to Yasar Kemal". Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008.

Perrier, Jean-Louis (1997-03-04). "Yachar Kemal, conteur et imprécateur". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 2008-08-17.

"Ölene kadar Nobel adayı olacağım". Hurriyet (in Turkish). 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

Norman, Roger (1997-06-05). "Yasar Kemal and the last of the nomads". Turkish Daily News. Hürriyet. Retrieved 2008-12-15. ...for Yasar Kemal has become perhaps the best known champion of human rights in Turkey, the godfather of freedom of conscience. He is no stranger to prison and currently has a suspended prison sentence hanging over him.

"Turkish author Yasar Kemal dies at 92". Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"Yasar Kemal, one of Turkey's best-known novelists, dies at 91". Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"Yasar Kemal: Author who came into conflict with Turkey for addressing human rights". Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"Usta yazar Yaşar Kemal tedavi gördüğü hastanede hayatını kaybetti!". Retrieved 10 March 2016.

"prominent-writer-yasar-kemal--laid-to-rest". Hürriyet Gazetesi. Hurriyetdailynews.

"Büyük usta son yolculuğuna uğurlandı". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

"Yaşar Kemal öldü! Yaşar Kemal kimdir?".

"Yaşar Kemal Kürtçe Düşünüp Türkçe Yazdı".

"Yaşar Kemal: 80 yıldır 'Bu adamlar niçin dağlardadırlar' diye düşünmedik!".

Jones, Derek. Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 2474. ISBN 9781136798641.

"Ukraine in Arabic | The famous Turkish writer and human rights activist Yasar Kemal died". arab.com.ua. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

"Dört ay tek satır yazamadım".

Bosquet, Alain. Yaşar Kemal on his life and art.

Asbarez, 1 October 2010: The Mass at Akhtamar, and What’s Next

Yasar Kemal, Master Turkish Novelist and Strident Political Critic, Is Dead

Kemal, Memed, My Hawk (New York: New York Review Books Classics, 2005), p. xii.

Taylor & Francis Group (2004). "KEMAL, Yashar". In Elizabeth Sleeman. International Who's Who of Authors and Writers. Routledge. p. 290. ISBN 1-85743-179-0.

Uzun, Mehmed (2001-01-22). "Thilda Kemal: The Graceful Voice of an Eternal Ballad". Turkish Daily News. Archived from the original on 2008-07-11.

"Thilda Kemal, wife and translator of novelist Yasar Kemal, dies". Turkish Daily News. 2001-01-19. Archived from the original on 2008-11-14.

"Efsane yazar Yaşar Kemal'i kaybettik". Hürriyet (in Turkish). 2015-03-01. Retrieved 2015-03-01.

Kayar, Ayda (2002-08-11). "Yaşar Kemal evlendi". Hürriyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-07-11.

"Yaşar Kemal'in cenazesine binler katıldı". BBC (in Turkish). 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

"Yaşar Kemal son yolculuğuna uğurlandı". Anadolu Agency (in Turkish). 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

"Yaşar Kemal'in oğlu konuştu: Bu bir mucize". A Haber (in Turkish). 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2015-03-04.

Birch, Nicholas (2008-11-28). "Yasar Kemal's disappearing world of stories". The Guardian (Books). Retrieved 2009-01-03.

Göktaş, Lütfullah (2007-06-30). "Yaşar Kemal'in Teneke'si İtalyanca opera". NTV-MSNBC (in Turkish). Retrieved 2008-07-11.

Büyük Larousse, vol. 24, p. 12448, Milliyet, "Yaşar Kemal"

Özkırımlı, Atilla; Baraz, Turhan (1993). Çağdaş Türk edebiyatı, Anadolu University, 105.

France, P., The Oxford Guide to Literature in English Translation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 624.

Çiftlikçi, Ramazan (1997). Yaşar Kemal: yazar, eser, üslup, Turkish Historical Society, p. 415: "KANIN SESİ: Dizinin son cildi KS, İM III ve IV'ün araya girmesi üzerine 1989'da tamamlanmış, aynı yıl Güneş gazetesinde tefrika edildikten sonra 1991 de kitap biçiminde yayımlanmıştır."

"Yaşar Kemal hayatını kaybetti" (in Turkish). Cumhuriyet. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

İnce, Özdemir. "Mutluluğun resmi de yapılır romanı da yazılır" (in Turkish). Radikal. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

Secular State and Religious Society: Two Forces in Play in Turkey, Palgrave Macmillan, 204.

Altınkaynak, Hikmet (2007). Türk edebiyatında yazarlar ve şairler sözlüğü, Doğan Kitap, p. 736

Köy Seyirlik Oyunları, Seyirlik Uygulamalarıyla 51 Yıllık Bir Amatör Topluluk: Ankara Deneme Sahnesi ve Uygulamalarından İki Örnek: Bozkır Dirliği Ve Gerçek Kavga Nurhan Tekerek

Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels 1997: Yasar Kemal, Buchhändler-Vereinigung, p. 63.

"En dag om året 1997 i Älvkarleby" (in Swedish). Anasys. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

"1997 Yaşar Kemal" (PDF) (in German). Friedenspreis des Deutschen Buchhandels. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

"Cumhurbaşkanlığı Kültür ve Sanat Büyük Ödülleri dağıtıldı". Milliyet (in Turkish) (Siyaset). Anka news agency. 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

"Yaşar Kemal'e Norveç'ten 'Bjornson' ödülü". Zaman (in Turkish). 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2015-03-02.

Çiftlikçi 1997, p. 29

"Yaşar Kemal'e büyük "nişan"". CNN Türk (in Turkish). 2011-12-18. Retrieved 2011-12-18.

"Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal gets Armenia's Krikor Naregatsi medal". Hurriyet. 2013-09-04.

"Uluslararası Yaşar Kemal Sempozyumu" (in Turkish). NTV. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

"Yaşar Kemal: Umutsuzluk umudu yaratır". ntvmsnbc.com (in Turkish). Anadolu Ajansı. 7 October 2009. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

"Umutsuzluktan umut üreten edebiyat çınarı Yaşar Kemal'i sonsuz yolculuğuna uğurluyoruz..." (in Turkish). Boğaziçi University. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

"Yaşar Kemal'e fahri doktora" (in Turkish). Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

..................................

Kurdish-Turkish writer Yaşar Kemal, who is known as the leading figure of the

genre of the “Village Novel” (Halman, 1970; Halman, 2006), is a novelist, journalist,

and folklorist (Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003). While critics have compared Kemal with

Tolstoy, Hardy, Steinbeck, and Faulkner, his wish has been to attain the spirit of the

Homeric epic (Halman, 1983). Indeed, it has been noted that some of his novels truly go

beyond the frame of a typical novel and are indeed epics (Boratav, 1980). He was

nominated for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, before any other Turkish, Arab, or

Iranian author (Andaç, 2003; Halman, 1977). He has also been successful as a journalist

and has been politically active from an early age (Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003).

Kemal is internationally recognized, especially acclaimed in France, where he

has been defined as an “epic writer,” England, the United States, and Scandinavia

(Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Naci, 1993). The four volumes of his most famous novel

Ince Memed (Memed, My Hawk) have been translated into over 40 languages (Halman,

1970; Halman, 2006). Several other novels have also been translated and printed in

various countries and some have been adopted as theater plays and scenarios, such as

Peter Ustinov’s film of Memed, My Hawk in 1984 (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

Kemal’s stories and novels focus on the lives of Anatolian villagers who are

nomadic or settled. His themes include blood feud, revenge, love, and daily hardships

faced by villagers. He often describes the difficulties that villagers dealt with in the

1950s with growing capitalism: Villagers had emerged from an agricultural era and they

found themselves in the modern age of mechanization where everything changed

100

(Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Köksal, 2001). Most of Kemal’s novels take place in and

around his home, Çukurova. In his most famous novel, Memed, My Hawk, Kemal

presents the bandit (eşkiya) Memed who defends villagers’ rights against the injustice

imposed by greedy landowners. The novel has been referred to as a Turkish Robin Hood

story (Halman, 1970) and has been described as presenting “the universal social

theme…protest of peasantry who are firmly bound to the soil, and whose world view and

entire life span are defined within patriarchal limits” (Al’kaeva, 1980, p. 69).

His extensive creative products include two story books—Sarı Sıcak (Yellow

Heat, 1952) and Bütün Hikâyeler (Collected Short Stories, 1967)—and a children’s

book, Filler Sultanı ile Kırmızı Sakallı Topal Karınca (The Sultan of the Elephants and

the Red-Bearded Lame Ant, 1977; Andaç, 2003). However, the bulk of his work consists

of numerous novels, experimental works, and collected interviews, presented in Table 6

(Andaç, 2003).

101

He has won 26 national and international awards. National awards include the

Varlık Novel Prize (1956), the 1966 İlhan İskender Award, and Orhan Kemal Novel

Award (1986), while international awards include the Best Foreign Book Award in

France (1978), the French “Big Jury” Best Book Award (1979), the International Cino

Del Duca Award (1982), the French Legion d’Honneur Award (1984), the 1996

103

Mediterranean Foreign Book Award (Perpignan, France), the 8th Catalonia International

Award in Barcelona (1996), Nonino Award in Italy (1997), and French Ministry of

Culture Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres Rank (1998) (Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003).

Kemal has also been awarded Honorary Doctorates at four universities: the French

University des Sciences Humaines in Strasbourg (1991), Antalya Mediterranean

University (1992), Frei University in Berlin (1998), and Bilkent University (2002)

(Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003; Yaşar Kemal: Biography, n.d.).

Biographical Information

Yaşar Kemal was born Kemal Sadık Gökçeli in the village Hemite (now called

Gökçeadam) (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Yaşar Kemal: Biography, n.d.). According

to official documentation he was born in 1926, which Kemal states is wrong: He

estimates his year of birth as 1923 (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). Kemal experienced

two traumatic events at a very young age. He lost one eye in an accident, and shortly

after that, when he was four and a half years old, he witnessed his father’s murder

because of a family feud (Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Yaşar Kemal:

Biography, n.d.). Kemal’s father had been a wealthy country gentleman, but after his

death, Kemal’s family lost their financial assets which left them in poverty.

As a child, Kemal was very interested in folklore and epics (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999). He completed his first year of elementary school in another village

(Burhanlı), after which his family moved to Kadirli, a town in Çukurova. He attended

elementary school there, while working in fields and cotton mills in the evenings

(Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Naci, 1993). He started middle school in Adana, where

104

he continued working in the evenings at a plant (Andaç, 2003). In the end of his third

year in middle school, he failed the class and was thus expelled from school, after which

he could not continue his education because of financial difficulties and started working

(Andaç, 2003).

Meanwhile as a teenager, Kemal also grew interested in various social and

political issues (Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). He became acquainted

with socialist leaders who lived in Adana. He met prominent novelist Orhan Kemal

(1914-1970) and read the poems of Nazım Hikmet (1901-1963) (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999; Kışlalı, 1987).

Kemal published his first book, a collection of folklore, in 1943. In 1946, at the

age of 23, he wrote his first short story A Dirty Story (Pis Hikaye) which he considers

one of his best works (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). From his teenage years until the

age of 28, he has had over 40 different jobs; for example, he worked as a cotton picker’s

clerk at a plantation, a clerk at a public library, a substitute teacher, a farm laborer, a

guard, a tractor driver, a sign painter, a mechanic, a foreman in rice fields, and a factory

worker (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003; Yaşar Kemal:

Biography, n.d.).

In 1950, Kemal was accused of being a communist spy and was arrested for

disseminating communist propaganda (Andaç, 2003). The police destroyed his most

recent novel and imprisoned and tortured him for a few months (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999). After his acquittal in 1951, he moved to Istanbul where he experienced a

period of unemployment, financial difficulties, and “a kind of depression” (Bosquet &

105

Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 77). He then started writing for the Newspaper Cumhuriyet

(Republic) (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). He changed his name and became wellknown

both as a journalist (the job he had for the longest period of time) and as a

novelist. Memed, My Hawk was on the best-seller list in England. He married Thilda

Serrero and had a son, Raşit Gökçeli, who is an architect (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999). After the coup of 1960, he was among the hundreds who were taken to

custody by the military regime (Ahmad, 2003).

In 1962, he entered the Workers’ Party of Turkey (Türkiye İşçi Partisi) and

became a member of the executive committee of the Central Committee and president of

the Public Relations Commision for eight years (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Kışlalı,

1987). That same year he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature (Andaç,

2003). In 1963, the government put pressure on the owners of the newspaper who had to

dismiss him, after which he focused on his career as a novelist (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999).

Kemal has been prosecuted by the government numerous times mostly for

supporting socialism. In 1967, he was arrested as the person in charge of the publishing

house Ant (Promise) for the printing of the book, The Main Book of Marxism, but was

acquitted (Andaç, 2003). After the ultimatum of 1971, which in practice was a coup, he

and his wife were arrested; he was imprisoned for a month, and his wife, for four months

(Andaç, 2003). In 1995, he was taken to court for “making separatist propaganda” in his

article Increase your Oppression (Zulmün Artsın) that was printed in the journal Der

Spiegel (Germany) (Andaç, 2003). Although he was acquitted, the following year, he

106

was sued again for “provoking the people to bear resentment and enmity” and “making

separatist propaganda” and he was sentenced to a year and eight months in prison, which

was delayed for five years. He appealed and was acquitted on the condition that he

would not repeat his crime for the next eight years (Andaç, 2003).

In January 2001, he lost his wife Thilda (Andaç, 2003). He remarried Ayşe

Semiha Baban in August 2002. Today, he lives with his wife in Istanbul.

Home Environments

Kemal’s home environment consists of his village, Hemite (now called

Gökçeadam), and its location, the plains of Cilicia (called Çukurova). Çukurova, which

lies between the Ceyhan (East) River and Seyhan (West) River, is between the

Mediterranean and the Taurus Mountains, near Adana in South Anatolia (Southeastern

Turkey) (Çakıroğlu & Yalçın, 2003). Three major cities are located in Çukurova: Adana,

Tarsus, and Mersin. It is a rich and fertile area in terms of agriculture, especially cotton.

Kemal also lived in Adana for several years. Adana has been a prosperous city

because of its location between the Anatolian-Arabian trade routes and on the IstanbulBaghdad

railway. One of Turkey’s centers of cotton industry, Adana manufactures

cement, agricultural machinery, vegetable oils, and textiles. Çukurova University was

established in Adana in 1973 (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007a).

The Interview

On July 4, 2007, at noon, I arrived at the apartment building where Kemal and

his wife have a flat. Kemal’s wife, Ms. Ayşe opened the door and anounced my arrival

to Mr. Kemal. He was sitting at his desk which was placed next to one of the large

107

windows in the living room presenting an amazing view of the Marmara Sea and the

Bosphorus. The living room was large and resembled a museum with the walls

decorated with beautiful paintings. There were shelves with books in various languages,

including various classics and books written by Kemal and about Kemal. The helves

were also decorated with little figurines and Kemal’s awards. Mr. Kemal had the

newspaper in front of him, which he had obviously been reading. He, his wife, and I

talked for a bit and they asked me more about what I was doing at Texas A&M

University. After a few minutes, Ms. Ayşe said she would leave us alone to our work

and left. Mr. Kemal was truly larger than life, not only regarding his physical presence—

he is very tall man (over 6 feet)—but also his personality. His presence is powerful and

he is full of energy and humor with a lot of laughter. One cannot help but notice his

large-framed dark-colored glasses behind which his right eye is closed shut (as he lost it

when he was a child). I was very nervous, because it was truly an honor to stand in front

of someone who is legandary. It was not just his success and his amazing creative

productivity, but also his life experience that was like a novel itself: A man who had

befriended Arthur Miller, former French Prime Minister Francois Mitterrand, former

Soviet President Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, and legendary Turkish poet Nazım

Hikmet. Our interview, which lasted a little more than an hour, went smoothly, with a

few interruptions by either the phone ringing or his wife coming in for a question. He

was very enthuisastic about the stories he was telling and it was obvious that he liked to

share his stories. I found him very approachable, despite the wealth of his life

experience. After the interview, he called his wife and said we were done. Ms. Ayşe said

108

that they were going to go to the pool and that they went often, which made me think,

once again, that Mr. Kemal truly had a youthful spirit.

Data Analysis

This section provides explanations of categories with example incidents (quotes),

inferences, and comparison with other data sources. The categories that emerged from

the interview were views related to creativity, Kemal’s personality, influential people,

the government, education (formal and informal), family, home environment, and the

people (halk) and the people’s language (see Table 7). Although one category, the

relationship between a country’s literature, writers, and socio-political issues, did not

emerge in our interview, it emerged in other interviews, and since it is closely related to

this study, is included in the findings.

1. Views Related to Creativity

In our interview, Kemal presents how he views creativity in five stanzas, only

one of which was prompted by me: (a) creativity is indescribable/unknown; (b) it has not

been studied enough; (c) it is extremely important; and (d) it needs inherent talent,

practice, and life experience. He emphasizes the importance of practice and life

experience and notes that people are important for the flourishing of creativity.

Indicating the importance of imagination, he talks about nature and its mysterious

quality as a source of inspiration. In other interviews, he talked about how he stimulated

his creative thinking (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999) and how much he worked on his

creative products (Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

109

Table 7

Findings on Kemal

Category Brief Information Number

of

stanzas

1. Views related to

creativity

Kemal explains how to develop creative skills and other factors

related to creativity.

5*

2. Kemal’s personality Nine personality traits emerged. 16

3. Influential people Seven people have been influential for Kemal’s life and

creativity.

11

4.Government Kemal explains his aversion to the government and how the

government interfered with his life.

6*

5.Education (formal and

informal)

Kemal severely criticizes the current education system and

makes a suggestion for the ideal system of education.

7*

6. Family Kemal briefly talks about his uncle, mother, and father. 3

7. Home environment Kemal’s home environment, the people, and customs, greatly

inspired his creativity.

5

8.The people (halk) and the

people’s language

The people, of whom he is a part, and their language inspired

Kemal’s creative productivity greatly.

8

9. The relationship between

a country’s literature,

writers, and

socio-political issues

Kemal indicates that literature and writers have a close

relationship with socio-political issues in a country.

**

Notes. * Stanza is long and extensive.

** Indicated in other interviews.

Kemal summarizes his views on creativity at the very beginning of our interview:

“Nobody can describe that (creativity)—they haven’t been able to describe that.” Noting

that not enough attention has been paid to the field of creativity, he emphasizes the

importance he places on creativity.

I think psychologists have not studied creativity enough… Creativity is the one

thing that people should deal with/ work with. The thing that is amazing is the

creativity of human beings… I mean we need to emphasize creativity the most.

110

Kemal indicates that creativity is the outcome of inherent talent (repeated twice),

practice (repeated three times), and life experience (repeated three times). He

emphasizes the importance of honing creative skills.

There is one thing I know: I’m pretty sure that there is a gene related to creativity

that exists in humans—a creativity gene. But this creativity gene is not

enough…. If you continue your creativity, your creativity will keep increasing….

(Creativity) doesn’t happen all of a sudden… Your creativity strengthens with

life experience/ as you live. Now when I write I am much better than I used to

be… This I know, this business (of creativity) develops with time.

Kemal expressed these ideas in other interviews as well (e.g., Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999; Kışlalı, 1987). For example, in his interview with Kışlalı (1987), he said that

in order for writers to become universal, they have to take on the role as the apprentice

and learn from masters both from their own society and from other societies.

From his different comments about creativity, it appears that he sees creativity as

something extremely special, almost magical. His very first response to my question on

creativity is that “nobody could describe it” to which he adds later on, “I mean, ‘What is

creativity?’ Creativity is what humans don’t know.” Twice, he points out that “creativity

is not easy” and that creativity is endless (“Like everything else, creating is also

infinite,” and “Creativity is infinite in mankind”).

Kemal notes that people have an important role in the stimulation of creativity:

“For folklore, poetry, and culture to exist somewhere—to be broad—the population

111

needs to be broad. In my folkloric years, I searched for secluded places. I went, I went, I

went, there was nothing in secluded places. There’s no material for folklore.”

Kemal emphasizes the role of imagination in creativity once, noting that

imagination is “Endless—it’s hard to believe how much it is.” In other interviews,

Kemal elaborated upon imagination and its role in human life in more detail, suggesting

that people create myths in order to cope with life (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Naci,

1993).

In our interview and others (e.g, Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Naci, 1993), he

has emphasized nature as a source of inspiration and has described it as alive and

mysterious. For example, in his interview with Bosquet (e.g., Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999), he said that he “had a passion for observing nature” (p. 76) and “A piece of

grass, the water pouring up from a spring, a butterfly on a leaf remaining motionless for

hours—all were pure miracles for me” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 81). (The

importance of nature and environmental setting is further discussed under the category,

home environment.)

In other interviews (e.g., Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), Kemal

talked about his creative process: “When I first began writing, I had to walk. I must have

convinced myself in time that I couldn’t write without walking. I have always walked to

write” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 117). If he did not need to “reflect a great deal”

he walked three kilometers (1.86 miles), if he needed to reflect more, he walked nine

kilometers (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 124). He also noted that he usually wrote

while standing. He noted that in order to concentrate on his work, he had made an effort

112

to leave his house and go to a distant place (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). For

example, he wrote most of his novels in Şile, a little port on the Black Sea just outside of

Istanbul, where he stayed at a hotel and wrote all day (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

Regarding his creative process, he also said that in order to create a final product,

he did extensive work. In the beginning of his literary career, he worked on a novel for

years, going through “crises” over the smallest details (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p.

121). But because of time limitations, he trained himself to do fewer revisions of his

work. He noted, however, that if he had time as he desired, he would like to “work over

a single sentence for a few days in a row” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 121). He

pointed out that he ponders on a topic for years and then starts writing on it (Andaç,

2003).

2. Kemal’s Personality

Another category that emerged from the interview is Kemal’s personality. Nine

different personality traits appeared in his various stories and examples: (a) a belief that

he’s had great luck; (b) curiosity; (c) intelligence and creativity as a child; (d)

persistence; (e) higher expectations for himself in relation to creativity; (f) sense of

humor; (g) outspokenness; (h) rebelliousness; and (i) dedication to literature. The first

four appeared once in the interview and the last one appeared at eight different points in

the interview. The first two traits were explicitly stated by him, whereas the others were

deduced by me from his stories. Information about Kemal’s personality appeared in a

total of 16 stanzas, none of which was prompted by me. He talked about his love for

literature as a child, his ability to stand up to authority, the fact that he expected more

113

from himself creatively, and his curiosity in other interviews as well (e.g., Bosquet &

Kemal, 1992/1999).

Kemal expresses his belief that he was a lucky person: “I’ve had great luck,

above everything, my whole life passed with luck, to tell the truth.” He says that one of

his characteristics that led him to learn, which in turn enhanced his creativity, was

curiosity: “I was a journalist. I travelled all over Turkey for 12 years. There isn’t a city I

haven’t visited... I was curious about everything. I was curious about people, I was

curious about trees.” In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), he

linked his desire to write to his curiosity, noting “My curiosity is limitless” (p. 81).

Kemal explains that as a child, he was called “Crazy Kemal” in his village

because he was a highly unusual, creative child. For example, he developed an ingenious

system in which he would cool down watermelons in the streams of the Savrun River

and then offer it to people who were afflicted by the extreme heat. He talked about this

event in his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999) as well, where he

pointed out that, while the literal translation for “deli” is crazy, in Anatolia it also means

“brave, generous, good” (p. 16). I see this whole story as an example of his intelligence

and creativity as a child.

The story of when Kemal declared himself a Folk Poet (Aşık) is an example of

his persistence. Aşık is a Folk Poet who wanders and plays the saz (a plucked string

instrument, popular in Turkey, Azarbiajan, Armenia, Iran, and the Balkan countries)

while reciting poetry (aşık also means “person in love”). When Kemal proclaimed

himself a Folk Poet (Aşık) and started wandering to various villages he was only 16

114

Although initially villagers saw him as a boy and refused his endeavours as a

Folk Poet (“They didn’t even give me a lamentation”), he was not intimidated or

disheartened; on the contrary, he said to himself, “‘I’ll show you who is an Aşık’.”

While the four personality traits mentioned thus far appeared once in the

interview, the other five traits appeared more often. Kemal suggests in two instances that

he had higher expectations for himself creatively, especially when he was young and at

the beginning of his literary career (fifth trait). For example, when he finished the first

volume of Memed, My Hawk (1955), he did not want to sign his name under it because

he was not satisfied with it: “Actually, it was because I didn’t like (it)—I was waiting for

The Wind From the Plain—that was in my head.” He did, however, end up signing his

name under the novel which became his most acclaimed work.

Kemal demonstrates his sense of humor (sixth trait) twice. While talking about

his youth, he says, “After meeting Şevket Usta—we’re communists, you know—we

said, ‘You’re a good communist,’ (he said) ‘What the heck do you know?’—we didn’t

know anything (Laughter).” He is making fun of himself as a young communist, which

is not a light issue for him since he has been a self-declared “militant socialist, formed in

Marxism” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 8).

Three of Kemal’s stories indicate that he is an outspoken person (seventh trait).

For example, as an elementary-school student, he was very direct and open with his

teacher.

The teacher kept asking, “Do you have shoes, do you have water, do you have

this-that?” I kept saying, “I’m only going to come to school for three months, I’m

115

not going to tire you/ wear you out”... “My teacher, I won’t bother you. I learn

quickly. Anyway, I’m going to write my folksongs, that’s why I’m learning

this”... Three months passed, I said, “My teacher, I’m leaving now. I’ve learnt it.

You can quiz me on it. Thank you for everything. Didn’t I tell you I would learn

it all in three months?”

Thus, even as a child he was able to not only go to an authority figure and tell him

exactly what he wanted, but also go to him afterwards and say “I told you so.”

The eighth trait that becomes apparent is Kemal’s rebelliousness, which appeared

three times. For example, as a child he stood up to his mother, who disdained Folk Poets

and thought it unfit for Kemal, when she burnt the saz he had bought with his own

money: “‘Well I’m going to be like Abdal-e- Zeyniki!’” (a famous Folk Poet) “‘Why are

you burning it?’” In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), he

talked about how he had stood up to his family and the village. In his interview with

Kışlalı (1987), he pointed out the importance of rebellion: “One of the greatest values of

human beings is rebellion. The rebellion of humans against nature, the rebellion of

person against person, the rebellion of humans against tyranny.”

The ninth trait, which appeared eight times, is probably Kemal’s most important

trait as a highly creative writer: extreme dedication to literature, specifically becoming a

Folk Poet, even as a child. For example, when describing his village, he says,

Amazing epic story-tellers came to the village. I was enamoured. All the children

slept, but I didn’t, I listened (to them) until the morning... I studied folklore, I

116

was also writing poems, I was racing with Folk Poets (Aşıklar)... I’m only seven

years old. I’m going to be a Folk Poet...

His dedication to this dream continued into his teenage years. When he was 15 or 16, he

went to the Folk Poet Güdümen Ahmet and asked to be trained by him.

3. Influential People

This category, the first of seven related to socio-cultural factors, contains

information on seven people who appeared in 11 stanzas, none of which were prompted

by me. The influential people include (in the order in which mentioned) Mr. Cevat

(editor-in-chief of the newspaper Cumhuriyet), a teacher from Cyprus who lent his

house, Mehmet Ali Aybar (1908-1995) (president of the Workers’ Party of Turkey), his

Uncle Tahir, the Folk Poet Güdümen Ahmet, Arif Dino (1893-1957) (his mentor), and

Nazım Hikmet (1901-1963) (poet and close friend). The two people whom Kemal talked

about most extensively were Mr. Cevat and Nazım Hikmet, each brought up three times.

Nazım Hikmet (1901-1963), who is known as the first modern Turkish poet, has been

acclaimed as one of the most important poets of the 20th century worldwide (Halman,

2006; Turan, 2002). He was imprisoned several times because of his Marxist views

(Turan, 2002). Although mentioned once, Kemal states Arif Dino’s importance as his

mentor.

The first person Kemal mentions is Mr. Cevat, the editor-in-chief of the

newspaper Cumhuriyet where Kemal worked for 12 years. Mr. Cevat was influential to

Kemal’s literary career; for example, it was thanks to him that Kemal put his name under

Memed, My Hawk when he did not want to: “I went to Mr. Cevat. He was very

117

saddened, ‘Why didn’t you put your name, my child? It would have been so good,’ he

said… So what Mr. Cevat said happened… Yaşar put down his signature! (Laughter).

That’s how it happened.”

Kemal makes the importance of his “amazing friendship” with Nazım Hikmet

obvious by talking about it extensively. Calling him “our (Turkey’s) Pushkin,” Kemal

indicates Hikmet’s influence on his creativity. He notes that he reads Hikmet’s books to

“learn Turkish” and presents Hikmet and Stendhal (1783-1842) as “the two men I love

most.” He expanded upon their friendship and Hikmet’s literary genius in other

interviews as well (e.g., Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Kışlalı, 1987).

Despite talking about his role as a mentor once, Kemal emphasizes Arif Dino’s

importance in his life, which he pointed out in other interviews as well (Andaç, 2003;

Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999): “Everyone has a teacher/mentor, Arif Dino is my

mentor. I owe my everything to him. He was a great man. Amazingly cultured. The

brother of Abidin Dino—a great poet. A great painter. An amazingly cultured man.

There is no other man like him in Turkey” (Dino’s greatest influence on Kemal is

explored under the category, education).

Another person who impacted Kemal, specifically his creative productivity, is

Mehmet Ali Aybar, the president of the Workers’ Party, who encouraged him and

showed great interest in his work. For example, when Kemal was planning to re-write

The Wind from the Plain (1960), Aybar persuaded him not to, thus having a direct

impact on one of his most important novels.

118

He said, “Look, Yaşar, I should have more experience in life than you. I’m older

than you are… Come on, don’t write it a second time. Make corrections and

leave it at that. Instead of re-writing it, write another book.” And I listened to his

word. If it hadn’t been for Aybar, it truly wouldn’t have happened.

Another influential person was a teacher from Cyprus who let Kemal stay in his

house for six months while he was gone. This had an impact on Kemal’s life, because

the teacher had numerous records which Kemal listened to and learned classical music

from. Kemal presents this event as an example of how lucky he has been throughout his

life.

I kept listening constantly, I didn’t understand anything—until I heard

Beethoven, then I understood a lot! (Laughter). No one knew (about him)

then...meanwhile I was listening to one of the greatest (musicians) on earth... I

ate a little but took the needle... The needle—since the gramophone was playing!

(Laughter) All day and all night I was playing it (Laughter).”

The Folk Poet (Aşık) Güdümen Ahmet was also an important person in Kemal’s

life, as he trained Kemal to be a Folk Poet. At the age of 15 or 16, when he told the poet

he wanted to travel with him to be trained, he accepted it: “I was educated by him by

travelling village by village... I listened to him, then later I started telling (epics).”

Güdümen Ahmet is also included under the category education.

The last influential person Kemal mentions is his paternal uncle, Tahir. Although

he does not directly talk about his influence, his stories suggest that his uncle had

influence on his life in general and his creative productivity. His uncle provided for him

119

and his family: “My uncle took me to Osmaniye, bought me clothes, shoes, whatever.

He also gave me money... He bought several notebooks and several pencils.” Kemal also

used some of his memories of his uncle in his novels.

If he was sad, angry, or nostalgic/had a longing, he would sit on a chair at home

and start singing folk songs in Kurdish... My uncle had a very beautiful voice...

He sang amazing Kurdish folk songs, “foreign-land” folk songs, he would tell me

all of it. I wrote of all this in my novels.

In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), he noted that after his

father’s death, his mother married his uncle.

In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), Kemal said that

his first wife, Thilda Serrero, was very supportive: “For her part, Thilda was always at

my side; she always supported me and withstood my poverty courageously” (p. 79). In

our interview, he mentions her in passing with praise (“…I came home, my wife

Thilda—you know my great translator…”).

4. Government

Kemal talks about the various ways in which the government interfered with his

life in six elaborate stanzas, three of which are in response to my questions. Kemal’s

strong aversion to the government, which he has expressed in other interviews as well

(e.g., Kışlalı, 1987), becomes obvious when he talks about the government’s interference

with writers’ lives. He notes that pressure from the government definitely had a negative

impact on the quantity and quality of his work. Although in our interview, he refers to

his leftist views three times in a joking manner, Kemal has been quite passionate about

120

his political stance, as he has indicated in other interviews (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999; İpekçi, 1971; Naci, 1993).

The one example of government interference Kemal gives most often (four

times) is the prevention of his books’ publication. For example, he points out that

because he had already been established as a leftist ex-convict, the government was

“very angry” when he won awards for his novels and did not allow publishers to print

them: “They (Varlık Publishing House) were going to publish the book, they didn’t.

They (the government) put so much pressure on them… nobody printed Memed, My

Hawk for a year.” Later he returns to this topic and expresses his astonishment at the

government’s intimidation of publishing houses, noting, “Now you’ll understand what it

means to be a writer in Turkey.” He talks about his experience with a publisher.

I sent them (stories) to Yaşar Nabi—the biggest publisher. He said, “I can’t print

these. I can’t print them politically (because of political reasons)” and he sent

them back to me. “You’ve written amazing stories,” he said, “it’s amazing.

Hopefully one day we can publish them.” But because of politics.

Calling the government “a liar,” Kemal expresses his strong emotions against the

government twice. When I ask about the impact of socio-political issues on creativity in

Turkey, he replies, “Well it is tyranny, the situation in Turkey. The things that are done

to artists—especially novelists—in Turkey is a horrendous tyranny.” He presents a

metaphor for Turkish writers, which he wrote as a story that appeared in Spanish,

French, and Turkish literary journals:

121

In Central Anatolia, in the winter, wolves which go hungry attack the barns…

(The villagers) catch one wolf. They don’t touch it… They take it and hang a bell

on his neck. They leave it. (The wolf) can’t come close to anything. It can’t come

close to other wolves or the villagers (Laughter). This is how it happens. I said,

they turned all the writers in Turkey into wolves with bells.

He adds that he lived in Sweden for three years because he was unsafe in Turkey: “I ran

away from here so they wouldn’t kill me.” Kemal expressed his strong aversion to the

government in other interviews as well (Andaç, 2003; Kışlalı, 1987).

Later, he notes that if it had not been for the government interference, he could

have written more and better. As an example, he notes that he had to work and make a

living for 12 years, during which he wrote only two-and-a-half novels. On the other

hand, when he was able to devote his time to writing, in 10 years he wrote 14 novels.

This account is ironic, however, because the reason for his leaving his job after 12 years

was the government, which had him let him go. Thus, although he expresses his

frustration with this incident, it was precisely that which led him to devote his time to

writing. So, what was then a negative event turned out to be positive for his creativity in

the long run.

Although in our interview, Kemal mentions his political views three times in a

joking manner, Kemal has emphasized the importance of his socialist views in other

interviews (e.g., Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; İpekçi, 1971; Naci, 1993). For example,

he said,

122

I am militant socialist, formed in Marxism. I say this in a very general sense, for I

have never allowed myself to be enclosed in any strict mold… I have always

struggled against the dogma built on Marx’s name. (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999, p. 8)

5. Education

Kemal’s comments related to education can be grouped into two: formal

education, which he strongly opposes, and informal education, which was provided by

his mentor, Arif Dino. He criticizes the education system as it is around the world and

suggests that education should take place through working and studying, producing, and

creating. He talks about the rector of the Istanbul University whose lack of respect upset

him greatly and compares him to the rector of the University of Oslo. He comments on

formal education in five stanzas, two of which were prompted by me, and informal

education in two stanzas without my prompt.

When asked about the impact of education on the development of his creativity,

Kemal tells the story of how he learned what writing was from a tradesman. He realized

that he could keep track of his poems through writing and thus, he decided to attend

elementary school for one year. He notes that the only positive factor related to formal

education was that it enabled him to read and write. He fondly talks about his elementary

school teacher, the only person he mentions related to his formal education, emphasizing

his concern for his wellbeing: “The teacher kept asking, ‘Do you have shoes, do you

have water, do you have this-that?’” He did not continue his formal education after

middle school.

123

..png)

.jpg)

Kemal notes that he realized how bad education was during his approximatelytwo-year

experience as a substitute teacher at an elementary school. He makes his

aversion towards education obvious.

They come to high school, there’s another trouble/ predicament, in university

there’s another kind of trouble/ predicament. This is not education—this is an

education of insult. They (schools, educators) are tyrannizing. What kind of a

school is this?! They start with a funnel. They put things in their heads with a

funnel. Then they (students) just forget it all. I mean, there can never be peace in

the education system.

He criticizes the treatment of children and youngsters, noting that they are not

treated as people. Calling Children’s Literature “disgusting,” he makes it obvious that he

feels strongly about this issue. Kemal grew up in an atmosphere that was liberating for

children; there was no distinction between adults and children regarding literature

(Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), which may be a reason for his strong sentiments.

Kemal also presents his idea of the correct educational system:

The education I think of is different. It was implemented in Village Institutes to

some degree... Now, Marx says this: education through producing. He said,

education through working/studying and producing. I have one more thing (to

that): education through working/studying, producing, and creating. And leaving

people completely free—not enslaving people. People who are slaves try to

create more slaves... there should be such education for all humanity. Education

through creating and producing.

124

He notes that there have been some advances in education in Sweden and the United

States.

Kemal then turns to how he was educated by his mentor, Arif Dino, and

compares his informal education to formal education.

I didn’t study pedagogy. I went to Adana. Everyone has a teacher/mentor, Arif

Dino is my mentor. I owe my everything to him… When I give speeches I boast

about it: You’ve come out of universities, I came out of the university of Arif

Dino. Who are their universities next to Arif Dino… When I came to Istanbul,

there were the students of a great professor, many great professors. They knew

Homer, but didn’t know who wrote the Iliad, but I knew it all by heart

(Laughter)… That’s why I’m against this education.

Kemal also experienced another form of informal education as a teenager, when

he was trained by the Folk Poet Güdümen Ahmet. Kemal learned about the art of FolkPoetry

by becoming a Folk Poet’s apprentice and watching him perform his art. In his

interview with Kışlalı (1987), Kemal pointed out the importance of mentorship and

training, stating that writers need to take on the role as the apprentice and learn from

masters both from their own society and from other societies.

Overall, Kemal’s comments are directed towards education around the world and

not specifically Turkish education. However, he does make a contrast between education

in Turkey and education in another country, which, although not related to what is taught

in educational institutions, is related to those in charge of educational institutions. He

125

brings up a comment that the rector of the Istanbul University made that upset him

greatly.

You know what the rector of the Istanbul University said here? “I will allow

neither Orhan Pamuk nor Yaşar Kemal to enter this university,” he said, “There

is no way I would let them in” he said. Would I come to your horrible university

anyway??

Here, Kemal refers to a comment the rector, Dr. Mesut Parlak, made in an interview,

where he said, “Orhan Pamuk and Yaşar Kemal cannot give a lecture in my university”

(Kaplan, 2007). Parlak, who considers himself a nationalist and a patriot, argued that the

two writers were traitors. In our interview, Kemal then proceeds to contrast that rector

with the rector of the University of Oslo, who drove three hours to personally pick

Kemal and his wife up from the airport, and expresses his anger.

(The other) says “I won’t allow Orhan Pamuk or Yaşar Kemal”…This is the

country of animals. The other man comes to greet me—he drives three hours

with his car, and picks me and Ayşe up and takes us to the university. Look at

Norway, look at these animals. He says, “I won’t allow into the university.” I

wouldn’t accept his doctorate!! Even if they offered me I wouldn’t accept it.

In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), Kemal noted that

he had wanted to become a scholar, which he does not mention in our interview.

Kemal’s dream had been to study folklore and ethnography of Eastern cultures, but that

he could not continue school. It is also noted elsewhere (e.g., Andaç, 2003) that Kemal

126

did not leave after middle school at his own will, but he had to leave school for reasons

unspecified.

6. Family

Kemal talks about his family, specifically his uncle, mother, and father, in a total

of three stanzas. Other than mentioning his uncle (explained under influential people),

Kemal refers to his mother once and his father twice, the latter whom he mentions in

passing. In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), he talked about

his parents in more detail.

Regarding his mother, Kemal explains her disdain towards Folk Poets: Since

Kurdish gentlemen had their own “Poets” (dengbej) to travel with them, she thought this

occupation was beneath Kemal’s social status, since he was the son of an Agha (Ağa), a

title given to those who have land or a certain status. Even though Kemal’s family had

lost their financial comfort after the death of his father, this did not change the fact that

Kemal was the son of an Agha. In his interview with Bosquet (Bosquet & Kemal,

1992/1999), he noted that his mother had been a very capable woman who had managed

everything and who had taken great care of him, adding that he “greatly admired her

way of dealing with people” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 31).

The first time Kemal refers to his father is in a joke. He was told he was the “son

of a great Agha,” and he responded, “‘Well he died a long time ago’ I said” (Laughter).

The second time he mentions his father is while talking about his stance against the

current education system: “I used to be a stutterer. I was with my father when he was

murdered. I was a stutterer until I finished elementary school. I was a huge stutterer, in

127

fact.” Although Kemal does not elaborate upon his father more, his death has a huge

impact on Kemal. Witnessing his father’s murder at the age of four and a half

traumatized him and caused him to stutter until he was 12 (Yaşar Kemal: Biography,

n.d.).

7. Home Environment

Kemal indicates that his village, the people, and customs greatly inspired his

creativity. In fact, most of his novels take place in and around Çukurova (Andaç, 2003).

In five stanzas, he emphasized the importance of his home environment, which consists

of his village, Gökçeadam, and its general location, the plain of Çukurova.

When asked about the factors that impacted the development of his creativity,

Kemal immediately starts talking about how his family immigrated from Van, a city in

Eastern Turkey, and settled at the Turkmen village of Gökçeadam. The Turkmens are

Turkic people, the majority of whom live in Turkmenistan and in neighboring parts of

Central Asia, including Turkey, Iraq and Syria (Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007i). They

speak Turkish and their numbers were more than six million at the beginning of the 21st

century. Kemal points out that he did not know of a difference between a Kurd and a

Turk and that groups from different backgrounds lived in harmony, which he noted in

other interviews as well (e.g., Andaç, 2003; Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

I never knew if I was a Kurd or a Turk. For a long time—I mean, at home

everyone spoke Kurdish, they didn’t know Turkish, having come from Van... I

went outside, I spoke Turkish, I came home, Kurdish. I didn’t even notice a

difference—I’m a Kurd, I’m a Turk—there was no difference...Only when I went

128

to Kadirli, when I went to the town, did I understand that Kurds were a seperate

people. I still didn’t perceive/recognize was I a Kurd or a Turk.

The culture at that location led Kemal to become immersed with epic storytelling

and poetry: “Amazing epic story-tellers came to the village. I was enamoured. All

the children slept, but I didn’t, I listened (to them) until the morning.” The people around

him gave him inspiration and provided material for stories and poems. His story about

how he and his friend crossed a river to go to the neighboring village for school is an

example of childhood experiences that fed his creativity. Various experiences as a young

adult in his village, such as working as a water-controller in rice fields, gave him the

opportunity to become immersed with nature, which was greatly inspirational to him. He

felt a connection with the Savrun Creek, for example, whose water is “is so clear, that

should (a page of) the Qur’an fall down to its bottom it could be read.”

In other interviews (e.g., Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Naci, 1993), Kemal

emphasized the concept of home. He said that he has always integrated the setting within

nature into his work, because he is “convinced that one can only attain truth by placing

man in his primordial frame of reference” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 129). He

expressed his love for his home environment by stating, “If I hadn’t learned how to read

or write, now I would have been in a village in Anatolia, telling epic stories and singing

folksongs” (Naci, 1993).

In other interviews (e.g., Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Kışlalı, 1987), Kemal

talked about the bandits around his village and their impact on his creativity, which he

does not mention in our interview. For example, until 1936 there were about 500 bandits

129

(eşkiya) around Çukurova and Kemal had dialogues with some of them (Kışlalı, 1987).

In fact, these experiences led him to create his most famous character Memed (from

Memed, My Hawk), who is also a bandit (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

8. The People and the People’s Language

Kemal points out the importance of the people and the people’s language for his

creative work in eight stanzas. With “the people,” Kemal is referring to Turkey’s “halk”

which can be translated as “people, community, public, folk” and refers to peasants,

workers, teachers, town people, villagers, excluding the rich and upper-middle class (for

example, “halk pazarı” is translated as “people’s market”). He indicates that the people,

whom he is a part of, their knowledge and culture have greatly influenced him and his

creativity (repeated eight times). He notes that he has used the language of the people

(repeated six times), which is different from the Turkish spoken in big cities, particularly

Istanbul, and has several different dialects. He points out that the creation of language

and changing the style of his novels is crucial for his creative work.

Kemal repeatedly notes the importance of the people (halk) for his creativity.

While mentioning nature as a source for inspiration, he adds,

I’ve learned this from the people (halk)—the people know it better than I do.

When you look at the Iliad, again it’s the people’s things—it’s all taken from the

people. It comes up to this day... Everything, the most beautiful things in nature

were told by the people.

While talking about how Nazım Hikmet got to learn about the people, Kemal uses a

metaphor where the people are equated to medicine: “…Nazım takes vaccination/shot of

130

the people (halk)… Nazım said, “Of course you are right. There is nothing richer than

the people for a writer.” Kemal emphasized the importance of the people (halk) in other

interviews as well (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999; Kışlalı, 1987; Naci, 1993). He said

that he did not believe in heroes and that the rebels (main characters) in his novels were

the products of the people (Naci, 1993).

Kemal contrasts the language (dialect) spoken in the city to that of the village:

“(In the village) I was in a—a beautiful language. I mean, (now) I’m in the city—

speaking with the people’s (halk) language is like poetry.” He suggests that speaking

with the poeple’s language brings a wealth of knowledge itself.

They say I am the one who knows the most in Turkey—everyone says it, I guess

it’s not unmannerly if I say it too. But what’s the reason? My language is the

people’s language. The Turkmens speak beautifully.

Kemal indicates the importance of creating his language by noting that “the

fundamental thing he is creating is language.” Kemal expanded upon his approach to

language in his writing in other interviews, noting that when he first started writing, he

explored different ways of writing one sentence and studied how various people

expressed themselves (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). As a teenager, he observed that

Folk Poets and story-tellers incorporated local expressions and their own use of language

into their stories (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 39). With a dislike to writing in the

same form or style, he commented that with every piece of literature, he wanted to

“create a new kind of narrative, beginning with a whole new language” (Bosquet &

Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 65).

131

9. The Relationship Between a Country’s Literature, Writers, and Socio-Political Issues

Although he does not talk about this topic in our interview, in other interviews

Kemal has suggested that a close relationship existed between a country’s literature,

writers, and the socio-political issues in that country (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999;

Kışlalı, 1987; İpekçi, 1971). His thoughts on this issue have been included in the

findings since they are closely related to this study. Kemal has called himself a “a

political writer” (Kışlalı, 1987) and has emphasized that his art could not be seperated

from his politics (İpekçi, 1971). He also suggested that writers had a responsibility to

their community: “Being a well-known writer obliges one to assume greater

responsibility. Because each country knows its particular problems, its writers find

situations related to these problems” (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999, p. 103).

Summary

In our interview, the topics upon which Kemal elaborated most were his views

on creativity, the government, education, his home environment, and the importance of

“the people” (halk) and “the language of the people.” In several instances he gave

examples of various aspects of his personality and talked about people who were

influential in his life.

According to Kemal, creativity is an indescribable and mysterious—almost

magical— phenomenon which, although not having been studied enough, is the most

prized possession of human beings. While creativity most likely has a strong genetic

component, it requires life experience and practice to reach maturity. Nature, with its

mysterious quality, is an important source of inspiration. Kemal noted that in order to

132

concentrate on his work, he retreated to a secluded place, and in order to think

creatively, he had to walk (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999). He indicated that he thought

about topics for years before he started writing about them (Andaç, 2003) and that he

had to work on his creative products extensively (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999).

Kemal openly expressed his aversion to the Turkish government and explained

how the government repeatedly interfered with his literary career. An avid socialist

(Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999), he has been passionate about socio-political issues

which are important for his creative work (İpekçi, 1971; Kışlalı, 1987). He also noted

that literature was closely tied to socio-political issues (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999;

Kışlalı, 1987; İpekçi, 1971) and that his art could not be separated from his politics

(İpekçi, 1971).

Kemal distinguished between formal education, which he strongly opposes, and

informal education, which he received from his mentor, Arif Dino. The ideal education

system Kemal envisions would promote learning through working, producing, and

creating. He criticized not just Turkish education, but education all over the world and

noted that he did not know of a country that had achieved the education system he

envisioned.

Emphasizing the impact of his home environment, Kemal pointed out that the

natural environment, the people, and customs were greatly inspiring and led to his

passion for epic story-telling and poetry. Repeatedly noting the importance of “the

people” (“halk,” referring to peasants, workers, teachers, town people, villagers), Kemal

emphasized the knowledge he has gained from the lives and culture of the people, who

133

have been the focus of his novels. Pointing out that he is one of “the people,” he stated

that he used the language of the people, which is different from the language (i.e.,

dialect) of the city. Indeed, his novels contain words and expressions used in Anatolian

villages that have not been recorded (Bosquet & Kemal, 1992/1999); in fact, linguist Ali

Püsküllüoğlu published a Yaşar Kemal Dictionary (Yaşar Kemal Sözlüğü, Toros Press)

in 1991.

Nine personality traits emerged from the interview. Kemal explicitly stated that

he had had great luck throughout his life and that he had been a very curious person. His

stories indicated that he had been a rebellious and outspoken person and the one trait that

was most prominent was his dedication to literature even as a child. Other traits were his

intelligence and creativity as a child, persistence, sense of humor, and his high

expectations for himself in relation to creativity.

Kemal presented seven people as having an influence on his life and creativity,

almost all of whom had a direct impact on his literary career by guiding and encouraging

him. One person was a close friend as well as a literary figure who influenced Kemal’s

creativity (Hikmet) and one person was his mentor (Dino). The fact that Kemal talked

about seven influential people suggests that other people, as a socio-cultural factor, was

important.

....................................................

Author Yaşar Kemal

Original title İnce Memed

Translator Edouard Roditi

Country Turkey

Language Turkish

Publication date

1955

Published in English

1961

Followed by They Burn the Thistles

Memed, My Hawk (Turkish: İnce Memed, meaning "Memed, the Slim") is a 1955 novel by Yaşar Kemal. It was Kemal's debut novel and is the first novel in his İnce Memed tetralogy. The novel won the Varlik prize for that year (Turkey's highest literary prize) and earned Kemal a national reputation. In 1961, the book was translated into English by Edouard Roditi, thus gaining Kemal his first exposure to English-speaking readers.

Plot

Memed, a young boy from a village in Anatolia, is abused and beaten by the villainous local landowner, Abdi Agha. Having endured great cruelty towards himself and his mother, Memed finally escapes with his beloved, a girl named Hatche. Abdi Agha catches up with the young couple, but only manages to capture Hatche, while Memed is able to avoid his pursuers and runs into the mountains. There he joins a band of brigands and exacts revenge against his old adversary. Hatche was then imprisoned and later dies. When Memed returns to the town, Hatche's mother tells him he has a "women's heart" if he surrenders himself. He instead rides into town to find his enemy, on a horse given to him by the townspeople. He finds Agha in the south-east corner of his house and shoots him in the breast. The local authorities hear the gunshots, but Memed gets away. Before Hatche dies she gives birth to Memed's son, who is also named Memed. The protagonist then must take care of his son.

Film adaptation

Main article: Memed, My Hawk (film)

In 1984, the novel was freely adapted by Peter Ustinov into a film, produced by Fuad Kavur.

................