Narrative Syntax in Kurdish Folktales

Abstract

Narrative analysis has become a fruitful area in different fields of knowledge. Narrative can be studied in literature, linguistics, stylistics, sociolinguistics, psychology, medicine, etc. The present paper aims at studying the narrative structure of three Kurdish folktales in a syntactic perspective, since the area of structural patterns that make up the Kurdish folktales has not got much attention of academic research.

To achieve this purpose, the three Kurdish folktales, ‘The Result of Greed’, ‘The King and Fate’, and ‘Strike, Strike, What You Saw is All What You Get’, are analyzed according to Labov’s narrative syntax. It is hypothesized that Labov’s syntax is applicable to the analysis of the Kurdish folktales narrative structure. The study has concluded that Labov’s model can be regarded as syntax for the Kurdish folktales as it is for natural (i.e., orally told) narratives.

Key words: Narrative, Narratology, Narrative Syntax, Kurdish Folktales

1. Introduction: Concepts

Narrative texts permeate our lives, and human beings are said to be always tale tellers. If we look at newspaper reports, history books, novels, short stories, or listen to someone telling us their experience about a specific accident they had, then we will have a complete image of what the term narrative means.

According to Trask (2007), narrative is “a text which tells a story…it relates a connected series of events…either real or fictional, in a more or less orderly manner” (2007:181). Crystal’s (2008: 320) definition to narrative states that “a narrative is a recapitulation of past experience in which language is used to structure a sequence of (real or fictious) events, [while] the study of narratives is called Narratology.”

Depending on these two definitions, one can say that novels, short stories, tall tales, folktales, etc. are all different forms of narrative. Our main concern in the present study is the folktales.

A folktale is a narrative “which has been handed down from generation to generation either in writing form or by word of mouth (Thompson 1977: 4). The Kurds have an amusing oral history and culture, part of which is represented in Kurdish folktales. This oral cultural knowledge is passed from a generation to another and it has an influence on the people’s social life. Recently, these kinds of oral arts have been recorded, written and published in Kurdistan. Some of them have been translated into world languages, especially into English. The three selected folktales are taken from a special issue of the International Journal of Kurdish Studies, which features Kurdish folktales from the Sulaimani and Kirkuk regions of Iraqi Kurdistan (Tofiq, 2005).

2. A Narrative Syntax

In his ‘The Transformation of Experience in Narrative Syntax’ the American linguist, William Labov (1972:354-96), analyzed a large body of recorded oral narratives. According to Labov, a minimal narrative is made up of a “sequence of two clauses which are temporally ordered”, that is, it

2

comprises two clauses which have a single temporal juncture (Labov 1972: 360-61), so any change in the order will result in a change in their semantic interpretation, as in:

1. (a)This boy punched me (b) and I punched him.

2. (a) I punched him (b) and he punched me.

The order of the clauses shows that in (1a) the boy first hit the speaker, and in (1b) the speaker took his revenge on the boy, while the reverse happened in (2a and b) respectively.

Labov (1972: 362) distinguishes between two types of clauses within the skeleton of the narrative: narrative clause and free clause. Narrative clause is a “temporally ordered clause”. A free clause is a clause which is not “confined in a temporal juncture.” It is free in a sense that is moveable; it can be moved anywhere in the story. The overall structure of complete oral versions of narrative in Labov’s syntax includes six elements each of which tries to answer a hypothetical question:

1. Abstract: What was this about?

2. Orientation: Who, When, What, Where?

3. Complicating action: Then what happened?

4. Evaluation: so what?

5. Result or Resolution: What finally happened?

6. Coda: It prevents any further questions regarding the story events.

Abstract

Usually narrators begin their stories with “one or two clauses summarizing the story” (Labov 1973: 363). The abstract signals that the story is about to begin and draws the attention of the listener. Syntactically, the abstract is realized in terms of short summarizing clauses provided before the narrative commences. Usually English folktales start with phrases such as 'once upon a time' as an abstract, which has an equivalent in Kurdish 'habu nabu' jarekia’ or ‘ajaj lj ajaj’.

Orientation

Orientation usually consists of some free clauses that orient the listener in respect of person, time, place, and behavioral situations. Orientation in the narrative is marked by past progressive verbs and adjuncts of time, place, and manner (Labov 1972: 364) about person, manner, and time—they make up the orientation section. The placement of orientation clauses is usually before the narrative clauses (Labov 1972: 364-5).

Complicating Action

Complicating action is the most important element in the narrative in which the narrative clauses are contained. A narrative clause usually conveys a series of events. Complicating action begins from the first narrative clause and ends up with a result. Formally, complicating action can be recognized by temporally ordered narrative clauses with verbs in the simple past or present (preterit verbs, in Labov’s (1972: 376) terminology). It is worth stating that this element is the core of narrative without which it is impossible to have a narrative (Labov 1972: 360).

Evaluation

Labov defines evaluation as “that part of narrative which reveals the attitude of the narrator” towards the events. It functions to make the point of the story clear. It is by this element that the narrator wards off the “so what?” question which the listener may ask (Labov 1972: 370). The evaluation is the most sophisticated and problematic section in Labovian story grammar. It is of two types: external and internal evaluation (Labov 1972: 371-72). External evaluation can be

3

identified, simply, when the narrator stops the flow of narrating and turns to the listener to tell her/him what the point of the narrative is, that is, why s/he is telling the story (Labov 1972: 370-71). It can also be expressed by indicating the reaction of the narrator to the events being reported, i.e., by quoting her/his sentiment when the action went off (Labov 1972: 371-72).

The internal (or embedded) evaluation is more complicated than the external one. As the word ‘embedded’ implies, the evaluative materials (or devices) here are woven into the narrative clauses (Labov 1972: 372). In the analyses of the folktales more will be exposed about this portion of the narrative syntax.

Resolution

Resolution is defined as the “portion of the narrative which follows the evaluation. If the evaluation is the last element then the resolution section coincides with it. It signals the end of the story proper. Resolution is the result of all of the narrative clauses (Labov 1972: 370).

Coda

Usually narratives end up with the resolution section, but for a complete narrative one or two free clause(s) are required forming what Labov (1972: 365) calls coda. The coda bridges the gap between the moment of the time at the end of the narrative proper and the present. It also closes off the sequence of narrative clauses and indicates that none of the events that follow are important (Labov 1972: 365-66).

To sum up, a complete narrative is summarized in the abstract, begins with an orientation, proceeds to the complicating action, is suspended at the focus of the evaluation before the resolution, concludes with the resolution, and returns the listener to the present time in the coda.

The Kurdish folktales in the present study will be analyzed to see whether or not they provide the answers for these six questions, as Labov claims that the oral narratives do.

3. The Analyses of the folktales

1. ‘The Result of Greed’

Abstract

In this tale, the opening paragraph can be considered as an indicator of the abstract section. The narrator prepares his/her reader or listener to him/her with the help of the first paragraph that the narrator is going to recapitulate a story. Most of the Kurdish folktales begin with a very unique fixed expression, (Habu nabu kas la Khuday gawratir nabu), dagernawa rozhak…(Once upon a time, No one was Greater than Allah, they say that once…. ) In the Kurdish community whenever this expression is heard, all the people realize that the utterer is claiming the floor1. The story preface may differ from variety to variety, storyteller to storyteller. So in the token, this tale starts with

They say that a long time ago there was a poor shepherd.

If we look at the verb tense of this first clause ‘They say…’ which is present simple, and the that clause ‘that a long time ago there was a shepherd,’ which is past simple we feel that we are

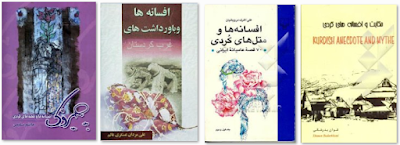

1 For further examples of this opening expression see:

1. Kurdish Folktale by Tofiq (2005)

2. Haqayat u Afsanay Millatan (The Folktales and Legends of the Nations) by Abdulla (2011).

3. Afsanakan wa degêrnawa (As the Legends Narrate) by Mawlud (2012).

This issue can be dealt with as a sociolinguistic fact, as well.

4

going to have a journey to a past event. The narrator links the past events to the present time. Above all, the title, ‘The Result of Greed’, is also another indication of the fact that the narrator is about to tell us a story about the outcome of greediness. One can say that the title and the first paragraph can be considered as a summary for the whole tale. In Labov’s narrative syntax, this is the form and function of an abstract.

Orientation

As we mentioned earlier, orientation tells us who, what and which are involved in the story, and where, when and how the story events took place. In the last part of the first sentence we are told that this story tells about a poor shepherd (who). Then comes the second sentence,

Every day he took his flock of sheep to a meadow far from the village, and there he pastured them.

Every day is a noun phrase that indicates the frequency (and syntactically it functions as an adverb of time), while his flock of sheep is another noun phrase that indicates the thing (what in Labov’s label). To a meadow far from the village sets the place where the story happened. These orientation elements are seen at the very onset of the tale and later in the story. There are other person, place, time, and manner indicators as well. Some of them are:

One day around midday (time)

near a pile of rocks, next to the rocks (place)

bread, milk, pot, snake, coin, (things)

his son (person, the shepherd’s son)

All of the above analyses prove that that Labov’s elements for orientation exist in the present tale.

Complicating Action

If we consider Labov’s definition for complicating action as the first two clauses which are temporally integrated we have to say that this portion of the present folktale begins with the first three clauses of the second paragraph:

a. One day around midday, near a pile of rocks, he took a sheep, 1

b. milked it into a pot,

c. and let it go.

Syntactically, there is a temporal juncture between the clauses a-c in that we can say that first he (the shepherd) took a sheep, second milked it into a pot, and third let it go. Another point is that the clauses are in past simple form which is also a very common feature of this narrative element.

One more thing about these three narrative clauses is that they are the basis for the rest of the narrative clauses in the current folktale. Let us see some more examples:

d. Putting the pot next to the rocks, he went

e. and sat down to eat some bread and drink some milk.

f. From after his eye spied a snake coming out from the pile of rocks.

g. It swallowed the milk in the pot

h. and then went back into the rocks,

i. took a coin in its mouth,

j. brought it,

k. and put it into the pot.

l. The shepherd came

m. and put the coin in his purse,

n. and he was so happy

o. his feet didn't touch the ground. (Tofiq 2005: 50)

In the above clauses d-n, one can notice that the clauses are all simple, with preterit verbs, in their structures. There is an exception in the beginning part of a and the end of n which can be

1 Like Labov (1972), we also use alphabetic format for numbering the narrative clauses.

5

regarded as evaluative devices, as we will elaborate it in the evaluation section of the current tale below.

Evaluation

The narrator of the present folktale employs various devices to evaluate its points. The story teller uses both internal and external evaluation from the very beginning up to the end of the story.

The title ‘The Result of Greed’ can be regarded a comment on the whole story. The narrator wants to say that it is because of greediness of the shepherd, first, and then his son, that they both are bitten by the snake. This type of evaluation is called external. From here and there the narrator hangs the events of the tale to reinforce the title. Some examples are:

he was so happy his feet didn't touch the ground.

but that night he didn't sleep a wink.

The son started thinking to himself, “By God, I have a silly father. Why should I sit around waiting for one coin a day? Why don't I just kill the snake and get the whole treasure for myself?” (50)

Recently your son attacked me and cut my tail off. When my spell wears off, I will be marred. Now, as a punishment for not keeping this secret in your heart, I will have to kill you too.” And she bit the man on top of his head and killed him dead on the spot. (51)

Looking at the above extracts again, we can identify some external and internal evaluation. The shepherd’s being so happy that his feet didn’t reach the ground is an external evaluation.

The use of non-assertive expressions, didn’t touch, didn’t sleep, why should, why don’t, not keeping, is a syntactic device by which the narrator comments on the events of the tale. Labov (1972:381-86) thinks that the use of negatives, questions, models, future, direct speeches, and imperatives is to a tool by which the narrator evaluates the tale. According to Labov the rituals like “By God…,” the shepherd’s going to pilgrimage, and cutting the snake’s tail1, are internal evaluations.

Another internal evaluation device is the use of foreshadowing and flashback. In the current tale the title is a foreshadowing because it foresees that the man’s greed will lead to the loss of his son and himself as well. Flashback is also used when the man returns from haj and says “One way or another, this son of mine must have done something to make the snake kill him.” Again in another direct quote by the snake that goes “Recently your son attacked me and cut my tail off.” This can also be called an embedded narrative, whose intention is also to give evaluation to the event(s). The snake continues by saying “now, as a punishment for not keeping this secret in your heart, I will have to kill you too.” The use of negative and future is again an evaluation marker. One last remark about evaluation section in this folktale is that one can find that its elements are scattered all over the whole tale, in all the parts of the narrative.

Resolution

As we said earlier, in Labov’s narrative syntax, a resolution provides an answer to the reader or listener’s question, “What finally happened?” Thus this can be the last narrative clause in the story. Actually, the narrative clauses of the present story can be divided into two sets of narrative clauses; the first set tells the story of the son; and the other set tells the father’s. On this basis we can say we have two resolutions as far as narrative clauses are concerned but in the end both resolutions are the same. The following are the two resolutions indicators for the current story:

1. What finally happened to the son?

p. The snake hissed

q. and attacked the boy,

r. bit him on the top of his head,

1 Culturally in some Kurdish rural communities, there is a belief that says “a snake never forgets its tail.” Thus, we can predict that the snake will take revenge on the shepherd’s son first and on his father as well. Therefore we can say that culturally it is a foreshadowing for what happens to the son and the father at the end of the story.

6

s. and killed him dead on the spot. (50)

2. What finally happened to the father?

t. And she bit the man on top of his head

u. and killed him dead on the spot. (51)

To be accurate and according to Labov’s narrative syntax, the resolution of the present narrative can be s and u. the syntactic structure of both of them is simple.

Coda

If we consider the title ‘The Result of Greed’ and the first paragraph as a starting point of present narrative, then we can say that with the death of the shepherd. The story comes back to its starting point and all the questions are fully answered as far as Labov’s six element narrative syntax is concerned. Syntactically, the narrative does not end with a free clause but with narrative clause which is u, as listed above. Thus one can say that it lacks a complete or a one-to-one coda.1

2. ‘The King and Fate’

Abstract

Like the previous folktale, the title, ‘The King and Fate’, and the first sentence of the first paragraph, they say represent the abstract element of Labov’s narrative syntax. The narrator uses the present simple tense verb ‘say’ in the independent clause of the first sentence and the past simple tense verb ‘was’ in the dependent clause.

They say that long ago there was a king. (Tofiq 2005:69)

Thus, we can say that this first sentence is a bridge between past and present and takes the reader or the listener to a journey of a king’s tale. This sentence can also be regarded as the whole tale’s preface.

Orientation

In this tale, the elements of orientation section are mentioned at the very beginning. The questions who, what, how, where, and when are answered at the very outset of the tale. Despite this, we also may see elements of orientation here and there later in the story, as the scenes require that. Thus we can say that main elements of orientation are in their own actual locations while others are delayed.

The story opens with a statement that long ago there was a king. This free clause gives information about when (through the adverb of time, long ago) does story happened and who (through the noun phrase, a king) is involved with it. Then it gives other pieces of information that represent orientation. Here reference is made to some of them:

His (i.e., king’s) wife, his son, his daughter, his vizier, his retinue and escort (representing who? in Labov’s syntax)

The king’s palace, his daughter’s room (where?)

in secret, With feigned reluctance (how?)

(Tofiq 2005:69-70)

Each of the above provides information about person, time, place, and behavioral aspects of the tale.

As the story goes on other persons, times, and places are mentioned as in:

Now the poor girl, left all alone, traversed field and plain, traveling several days and nights, and her clothing was ripped and shredded by thistles and thorns. One evening she went into a patch of wild straw berries to rest. The next morning, by chance, a prince arrived with a lot of dogs to hunt. When the dogs got near the

1 In some Kurdish folktales, especially the ones re-narrated and collected by Mawlud (2012), the coda can take a fixed form. The narrator also ends his story with “Crashm dra u heechishm penabra!” (I have my shoes torn, and benefited nothing). In such tales, the coda is very clearly stated.

7

patch of strawberries, they started yelping and baying. ''There must be something here,'' the prince said to himself. When he went forward, he looked and saw a beautiful young woman curled up, but she was wearing torn and tattered clothes. ''What are you?'' he asked. '' Are you a demon? a fairy? a human being? or what?''

(Tofiq 2005:70)

In the above extract, the items in bold face all represent elements of orientation. The adverb of time now and the noun phrases one evening and the next morning are all to show when the events they accompany took place, functioning as an adverb of time. The reader might think that now is for present tense not past. This is right but now or we can say present tense markers can be used in narrative discourses or texts for giving vividness to the events taking place, as it does in the present scene1. The noun phrases the poor girl, a prince; the dogs, a demon, a fairy and a human being are providing who and what elements to the story. In the same token, field and plain are for giving an answer to where question. And all alone and by chance, and with a lot of dogs show the manner of the verbs each of them accompanies. It is worth mentioning that the verbs in progression, i.e. –ing form, also serve as orientation markers (Labov 1972:364). The prepositional phrase near the patch of strawberries is another cue of where element in Labov’s orientation.

Complicating Action

The narrative clauses in the present tale, which are the main part of a tale, are numerous. We can say that the first sequence of two clauses which are temporally ordered are at the very beginning of the tale narrating that the kings wife dies:

a. His wife died

b. and left him with a son and a daughter.

(69)

As it is apparent from these two clauses that the death of the king’s wife happened firstly and then leaving the king and her son and daughter alone happened as a result of it secondly. The first action caused the second action.

Other narrative clauses will be:

c. All provision for the king's journey were made,

d. and he set out with his retinue and escort.

From the present sequence of these two clauses, one can say that c is prior to d not only structurally but semantically as well. If we change the order of these two narrative clauses and say He (The king) set out with his retinue and escort, and all provision for the journey were made, it will, though syntactically nothing is wrong with it, be semantically illogical, while the other way around is both syntactically and semantically is perfect. The same is correct for the rest of the following narrative clauses:

e. The prince took the cloak from his back

f. and gave it to her.

g. She put it around her shoulders

h. and came out of the strawberry patch.

i. The prince said to his father, ''I want you to marry me to this girl. Although she is a servant in our house, she is an intelligent and educated woman.''

j. and he married the girl to his son.

k. After a year God gave her a son

l. and she became even more beloved.

1 The use of present tense and present indicators in narrative is a very important technic and dramatic feature to the scenes of the tales and it is known as historical present.

8

Like a-b and c-d, the same relation exists between each of e-f, g-h, i-j, and k-l. The syntactic structure of the clauses of ‘The King and Fate’ is simple, with the only exception of the i clause, which will be topic for evaluation section. In all of the narrative clauses, the only tense which is used is past simple. Thus, the narrative clauses are in accordance with Labov’s narrative syntax.

Evaluation

In the current tale, the evaluation elements are found everywhere and the narrator uses various means by which the points of the story are cleared and the Labov’s “So what?” question is answered. The narrator, like the previous narration, makes use of both external and internal evaluative devices.

As usual, first we will explain the external devices. The situations and events where the narrator suspends the series of the stories, and uses external evaluation are mainly the following:

The king decided not to marry again so that his children would not be subjected to a stepmother. (69)

Here the narrator, through the free clause in bold face, explains and comments why the king decided not to marry another woman. Labov (1972: 392) calls such evaluative device “explicative”. In the Kurdish society, it is known that a stepmother is not kind with her stepsons and stepdaughters. Another direct and external evaluation is apparent in the free clauses of the following extract:

A few days passed. The vizier had a desire for her, and one day he attacked her in secret and said, “I want you to lie with me. If you don't agree to do it, I'll come up with a plan that will make your father cut your head off!” “Vizier,” the girl said, “you are in my father's place. Why are you saying these things? My father has entrusted me to you for safekeeping,” These words had no effect on the vizier, who kept insisting. There was nothing the girl could do but force him out, and she never again allowed him to come there.

(69)

Here the narrator tells the narratee or reader how lusty the vizier was towards the king’s daughter while he had been entrusted by the king that means he was in the place of her father, but he commits treason against his king. One more direct evaluation will be:

Now the poor girl, left all alone…..

(70)

He (the tea maker) was a really good worker and pleased the king highly.

(71)

The narrator also uses other devices by which indirect or embedded evaluation is made from the beginning up to the end of the tale. The outstanding device of this purpose is the use of direct speeches; the narrator comments the events via the characters’ speeches as in:

The king had completed trust in his vizier, and therefore he summoned him and said, “I'm going on the pilgrimage, and I'm taking my son with me, but I am going to entrust my daughter to your safekeeping.”

“Your Majesty,” the vizier said, “your daughter will be like my own. You go, and Godspeed.”

A few days passed. The vizier had a desire for her, and one day he attacked her in secret and said, “I want you to lie with me. If you don't agree to do it, I'll come up with a plan that will make your father cut your head off!”

9

“Vizier,” the girl said, “you are in my father's place. Why are you saying these things? My father has entrusted me to you for safekeeping.”

With feigned reluctance the vizier replied, “Your Majesty, what can I say? This daughter of yours wouldn't heed me, and she indulged in all sorts of lasciviousness, turning her house into a house of ill repute to which all and sundry had access.”

When they came to a spring, the brother said, “My good sister, I know you are purer than a rose petal. Therefore I am not going to kill you. I'm going to set you free here. Go wherever you like.”

(69-70)

Through the above quoted speeches the narrator comments on the fact how disloyal, untrue, treasonable the vizier was towards the king and his daughter while the king considered him trustworthy. The narrator also declares that king’s daughter is innocent and the vizier is a slanderer. At the end of the story, when the king’s daughter disguises herself pretending to be a tea maker, narrates her own adventures, all of her narration is in direct speech (see pages 72-73 from the story). Such types of embedded stories, i.e., stories within stories are good evaluative device by which a narrator can assess the events and they also elongate the story events. Another point is that the embedded narrative can also be studied separately according to Labov’s syntax and it contains all the six elements of a narrative. Here, we just refer to the opening sentences:

“Your Majesty,” he said, “they say that once upon a time there was a king whose wife died, and he was left with a son and a daughter. The king did not marry again, and the boy and girl grew up. Then the king went on the pilgrimage, taking his son with him, and he placed his daughter in the keeping of his vizier. After the king departed, the vizier desired the girl and wanted to rape her, but the king's daughter escaped.” At this point the king pricked up his ears and said, “Be quick, my son, and tell the end. This is just like something that happened to me.” The tea maker said, “King, this is a story. Listen and you'll find out what the end is.” Then he continued and said, “When the king returned from the pilgrimage, the vizier went out to greet him and slandered the girl. The king ordered his son to go take his sister far from town and cut her head off.”

(72)

Another linguistic device for indirect evaluation is the use of negatives and hypothetical expressions. Some examples are:

The king decided not to marry again so that his children would not be subjected to a stepmother. (69)

Hearing these words, the king went mad with anger and, on the spot, ordered his son to take his sister far from town, cut her head off, and bring her blood-drenched clothes back because the king did not want to lay eyes on his evil daughter. Although the prince knew that his sister was pure and had not done any such thing, there was nothing he could do but obey his father's order. He went to his sister and explained the situation to her. (70)

The man agreed. No sooner was she outside than she started running as fast as she could. Some time passed and the woman did not come back. The man went outside and searched this way and that. Neither

10

could he find any trace of her nor did he know in which direction she had gone. (71)

According to Labov’s syntax, all the negatives and modals, not to marry, would not, did not want, had not done any such thing, nothing, could, did not come back, and neither could…no did, in the above extracts are showing that the narrator comments on the context around which the negatives and modal verbs occur.

The use of questions is also one of the devices by which evaluation is performed, as in:

When the vizier came before the king and kissed his hand, the king asked, “Vizier, how is my daughter? During my absence have you taken good care of her and watched over her?”

(69)

“What are you?” he (the prince) asked (the king’s daughter). “Are you a demon? a fairy? a human being? or what?”

(70)

Many intensifiers have also being used for evaluating various situations and events. Some of them are:

All provision for…

the vizier and all people of the town (69)

all sorts of lasciviousness

the girl left all alone…. (70)

In the present narrative some imperative expressions have been utilized to provide assessment and comment on the events and this is again a fruitful device in Labov’s syntax for evaluation element. The followings are example for such device:

“Don't lie to me,”

“Get out of my sight”

“Get out, you filthy cur!”

“Go, and God be with you.”

“King, this is a story. Listen and you'll find out what the end is.”

Let’s go back to the adventures of the woman.

(71)

Religious rituals also play an important role in providing cues for embedded evaluation as far as Labov’s narrative syntax is concerned. In the current narrative, like the previous one ‘The Result of Greed’, the narrator refers to some terms like, going to pilgrimage, the dervish and drum (known as darwesh and daffa in Kurdish Language). Other examples of ritual expressions are:

“By God” she answered, “I'm not a demon or a fairy. I am a poor wandering woman, and I want to find work with some decent person and make my living.”

(70)

How far she went no one but God knows, but she came to her father's own city.

(71)

In Labov’s narrative syntax, the use of correlatives such as be…ing even the appended participle, v-ing alone, which shows that an action coincidently occurs with another, is an external evaluative device (Labov 1972: 387-88). Examples of correlative in the present tale are:

Hearing these words, the king went mad…

Weeping, the girl followed her brother out of town.

When the dogs got near the patch of strawberries, they started yelping and baying.

(70)

The next day she came across a farmer working in a field. (71)

11

Such use of the correlatives can serve to suspend the listener or reader get ready for another action to happen and as a result the narrator evaluates the events.

At the very end of the story, and more accurately to say, after the king’s daughter finishes her adventurous experience, the narrator suspends the narrative and comments on the reaction of the personal narrative of the tea maker by saying:

The king was overcome with grief, as his head spun as a result of this story. (73)

Till this point, the narrator has been evaluating the narrative events by different devices referred to throughout this section, and by the end of the last extract the evaluation section ends and we will come to the resolution section.

Resolution

According to Labov’s narrative syntax, the last narrative clauses come exactly after the evaluation element ends. In this case, the following narrative clauses represent the resolution element for the ‘The King and Fate’:

m. The tea maker took off his turban,

n. and abundant long hair spilled out.

o. “Father,” she said, “I am your daughter, and that dervish is my husband. That groom is the traitor to my husband who killed my infant son, and this is the vizier who slandered me.”

p. at the king's command, the vizier and the groom were beheaded.

(73)

The above narrative clauses, in Labov’s sense, provide an answer to “what finally happened?” and syntactically the structure of these clauses, m-p, like the narrative clauses of the complicating action section, is simple.

Coda

The final narrative clause p tells us what exactly happened after the maker tells his story and discloses himself as the king’s daughter. The listener might still want to know more about the rest of the royal family. Thus the narrator continues and says:

… and the king's daughter, her husband, her father, and her brother rejoiced in each other.

Through this simple sentence the narrator ends the story up and brings the narratee and reader to the point where s/he started telling the story of the king’s family and their fate. All the five questions in Labov’s narrative syntax can be fully answered. This final sentence is similar what Black (2006:40) emphasizes that a code includes a sentence like and they lived happily ever after. Accordingly, we can say that this end of this tale has a very typical coda, as it:

1. Gives a complete closure to any further questions and at this point we can realize that all five questions are fully answered.

2. Brings us, as listeners and readers back to the present time, by knowing the destiny of the king’s family.

3. Tells us that the bad is punished and the good is rewarded!

4. Gives us a lesson that the treason and disloyalty, no matter how long it is concealed, one day will be divulged!

At this point, we can say that Labov’s syntax is highly related to the semantic and pragmatic aspects of that narrative as well because this model does not only concern the mere syntactic surface structure but it also deals with the logical and deep structure of the narratives.1

1 Thus we can say that the narrative texts have deep structure and surface structure as Noam Chomsky asserts that the sentence syntax has such structures.

12

3. ‘Strike, Strike, What You Saw Is All What You Get’

Abstract

Like the other two previously scrutinized folktales, this tale has a very simple sentence within the first paragraph representing the abstract cue in Labov’s narrative syntax:

They say that once upon a time Sultan Mahmud disguised himself by putting on dervish clothes and went out to roam around the market and lanes of the city.

(73)

Via this paragraph, narrator drags the attention of the listener and reader to be aware of the fact that a story is about to be told. The part which is in bold is a common abstract marker in most of the Kurdish folktales, and the in present simple tense in They say and the fixed expression once upon a time provide a bridge between the present moment and the past events of tale. Another point about the first sentence in the first paragraph is that it sums the whole narrative up. Thus, abstract is fully found and well provided in the current narrative.

Orientation

The orientation elements found in this tale are few, especially the persons element, because of the tale’s being short in comparison to the previously scrutinized one. Despite this, there are ample elements to meet the needs of the orientation in Labov’s sense.

After the abstract of the story, the narrator relates:

Sultan Mahmud disguised himself by putting on dervish clothes and went out to roam around the market and lanes of the city.

This sentence, though in the text, it is a part of a larger sentence, gives information about person (Sultan Mahmud), thing (dervish clothes), and place (the market and lanes of the city) and manner (putting on dervish clothes). And these are all orientation elements. Another orientation cue in the sentence is the –ing form of the verb put, by putting on.

As the story goes on, the narrator gives further orientation information and introduces further characters. In the second sentence,

By chance, he passed by a blacksmith's shop, and he listened in, somebody inside was pounding away at something and saying, "Strike, strike, what you saw is all you'll get." The sultan, perplexed by these words, said to himself, "I have to find out what is the secret of these words."

(73)

The blacksmith’s shop, pounding, and saying are all orientation markers. In the second paragraph on there is another person introduced in the tale, the blacksmith. At the end of the story, the narrator mentions the sultan’s servants twice, earlier to this the mention of the beggar is also a cue. Thus, all in all, the orientation is well provided for this tale.

Complicating Action

The first narrative clause in this narrative is in the first sentences of the first paragraph:

a. Sultan Mahmud disguised himself by putting on dervish clothes

b. and went out to roam around the market and lanes of the city.

The clauses a and b are temporally ordered; first Sultan Mahmud disguised and then he went out. Other narrative clauses c and d, like a and b, are marked by simple syntactic structures are:

c. he (Sultan Mahmud) knocked at the door,

13

d. the blacksmith opened it for him.

The rest of the verbs of clauses in the current tale that relate the exact events are in simple tense and they are simple in their syntactic structure. The narrative continues with following narrative clauses:

e. “I'm a poor wayfarer,” the sultan said, “Maybe you could let me stay the night.”

f. “Of course,” the man said. “Please come in and be my guest.”

One might say that this pair, e and f, seemingly do not consist of two but more than two clauses. But in actuality every quoted speech stands for a narrative clause (Schifrin 1981: 46). Besides, every speech performs an action as far as Austin’s speech act theory is concerned. In the same token many similar narrative clauses to e and f are found in the rest parts of the story. Suffice to say that all of these narrative clauses prove that there are enough clues of complication action elements in the story under scrutiny.

Evaluation

Unlike the other two tales, the present story contains only one type of evaluation. It almost completely lacks the external evaluation. It only contains the internal one. The narrator does not evaluate the tale himself directly but via the speeches or the actions of tales characters indirectly. Through these evaluative devices the narrator comments on the events.

As an internal evaluation element, intensifying and emphasis is one of the effective devices in Labov’s narrative syntax. Labov (1972: 379) thinks that repletion is though simple in a syntactic point of view but effective as it intensifies and suspends the actions. In the current narrative, the title, ‘Strike, Strike, What You Saw Is All You'll Get’ has been repeated several times in the story parts: in the beginning, middle, and even the story ends with this expression. Thus, the narrator wants to say that this expression carries the complete meaning and theme of the tale. Within this expression we also have the repetition of the word strike.

In this same expression there are two other internal evaluation devices: the use of imperative mood and present and future tense. The verb ‘strike’ is used as an imperative. The verbs is and will contracted in the text as’ll can be cues for an evaluation.

The title can also be regarded as a direct quotation and direct quotations can be a device for evaluating the event. The narrator here indirectly wants to say that is in vain to get worried much about your worldly life and you cannot, like the blacksmith, change your destiny as it is prescribed by God.

Non-assertive expressions, negative and question have been also used in the story as in the following extracts:

Sultan Mahmud couldn't keep himself from asking, "If it's not impolite, sir, what do these words mean?"

(73)

But it didn't do any good. Sultan Mahmud wouldn't leave him alone.

It wasn't long before a beggar knocked on the door and asked for charity.

(74)

The dream of the blacksmith and his comment can also be, indirectly, an embedded evaluation:

"Brother," he said, "these words I say are the result of a dream I had. One night in a dream I came across a mountain. I looked and saw that the mountain was full of holes, and water was coming out of the holes. Water was gushing out of some of them, but it was only dribbling out of others. Then I saw an Arab man bathed in light.

'My friend,' he said, 'these are the destinies of people. Everyone who has a lot of water here has a great destiny earmarked for him and consequently is rich.

14

Everyone whose water is scanty here has little destiny and a poor,' 'All right,' I asked, 'where is mine?' He took me by the arm and led me to a rock in which there was a crack. A little water was oozing out of the crack. 'This is your destiny,' he said.

"When I woke up realized that all my effort was in vain. What had been fated to me was all would get. Many times I worked all day without making any money. For a long time now I have taken that dream to heart and realized that I am a poor and am not going to get any richer. That's why I have made it a custom to repeat those words."

(74)

This dream is an evaluation because:

(1) it gives the reason why the blacksmith repeats these special words;

(2) it is quotation; and

(3) it is flashback for what had happened and foreshadowing what will happen in the end. Labov (1972) considers flashback (and foreshadowing) as evaluative device(s).

The narrator, through the blacksmith’s comment wants to say that humans cannot gain in life more than what is fated or destined by God, and this fact has been reinforced throughout the whole tale, from the title to the very end. This can also be regarded as an indicator of ritual belief which is again a clue for internal evaluation. Another ritual concept is the sultan’s disguise as dervish twice in the story.

Resolution

As far as Labov’s syntax is concerned, the resolution element of the current tale is when Sultan Mahmud went to the blacksmith’s home for the second time to check why he is still repeating the same words. Thus the following narrative clauses indicate the end of the story:

g. The sultan was very surprised by this,

h. and that night he disguised himself in dervish clothing

i. and went to the blacksmith.

j. The sultan sat down.

k. Finally he asked, "Did they send you a gift from the sultan's house? A few days ago they put a roasted chicken on brass platter and sent it."

l. "Yes," he said, "they sent me the food, but a beggar came to me, and I said to myself, "I've eaten a crust of bread. I won't eat this; I'll give it to the beggar."

m. In utter astonishment Sultan Mahmud said, "It's true, whatever is fated comes to be." Then he said, "Dear sir, I am Sultan Mahmud, and that chicken I sent you was stuffed with money. God didn't fate it to you. It's clear that your dream was true, and you're right to say, "Strike, strike, what you saw is all you'll get."

(74)

Like the other narrative clauses, there is a logical or sequential relation between the clauses g-m. For example the clause g happened first then clause m. We can even say that there is a causal relation between the two as well; the first action caused the second to happen. For the exact answer for ‘what finally happened?, we can say that m narrative clause is the only right clause to do carry the answer.

Coda

In narrative syntax of Labov, the coda functions as an indicator of the full end of the story and coda takes the reader or listener to the point where the narrator started the story for the first time. Accordingly, we can say that because the current story starts with “Strike, Strike, What You Saw Is All You'll Get” as it is title and strangely the story ends with the same expression. Thus the listener or reader has been taken back to the point where the story started first. Another proof is that the lesson that we can learn from the tale is clarified and presented in m clause.

15

4. Conclusion

The study concludes what has been hypothesized that Labov’s syntax elements, abstract, orientation, complicating action, evaluation, resolution and coda are all available in the three Kurdish folktales. This does not mean that all the tales have the same linear structure. It is true that all elements of Labov’s elements are found in the tales but they do not have similar order, specially the evaluation because it has been scattered over the rest of the other five elements. As it has been seen in the analyses of the complicating action sections of all the three tales, the syntactic structure of the narrative clauses is very simple and absolutely meets Labov’s pattern and condition of clauses that tell tales. In the analyses of these three narratives, it has been also concluded that Labov’s narrative does not only pertain the mere surface syntactic structure of the tales but the deep syntactic and semantic structures of the elements in general and of the evaluation and coda elements in particular.

References

Abdulla, I. (2011). Haqayat u afsanay millatan (The folktales and legends of the nations).Erbil: Ministry of Culture and Youth Press.

Black, E. (2006). Pragmatic stylistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Crystal, D. (2008). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics (6th ed.) Oxford: Blackwell.

Labov, W. (1972). The transformation of experience in narrative syntax. In Labov, W. (Ed.), Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular (pp. 354–396). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mawlud, A. Kh. (2012) Afsanakan wa degêrnawa:komala afsana u haqayatkê kurdawarya (As the legends narrate:A collection of Kurdish legends and folktales ). Erbil: Rozh-halat Press.

Schifrin, D. (1981). Tense variation in narrative. Language, 57(l), 45-62.

Thompson, S. (1977). The Folktale. California: California University Press.

Tofiq, M.H.(2005) ‘The Result of Greed’. In Tofiq M.H.(2005). Kurdish folktales. (pp 50-51). Suleimani: Ministry of Culture Translation House.

______________‘The King and Fate’. In Tofiq M.H.(2005). Kurdish folktales. (pp 69-73). Suleimani: Ministry of Culture Translation House.

______________‘Strike, Strike, What You Saw Is All What You’ll Get’. In Tofiq M.H.(2005). Kurdish folktales. (pp 73-74). Suleimani: Ministry of Culture Translation House.

Trask, R.L. (2007). Language and linguistics: The key concepts (2nd ed.).New York: Routledge

16

Kawa Abdulkareem Rasul, PHD in English

Erbil Polytechnic University, Iraq

Ismail Abdulrahman Abdulla, MA in English

Dep. of Information and Library, Erbil Administrative Technical Institute,

Erbil Polytechnic University, Iraq

Date of Submission: 9 February, 2015

Date of acceptance:

-researchgate

Titles are examples of Hundreds of Kurdish legends and stories: (Their tall text on the Internet).

Tale 1. Dancing plowman

Tale 2. How to pinch off a goose

Tale 3. Baluli Zana and pitcher of gold

Tale 4. Ali's pride

Tale 5. My dream

Tale 6. Test by gold

Tale 7. Moses-pehambar gives his advice

Tale 8. If the salt is getting rotten

Tale 9. Lucky poor man

Tale 10. Human's life

Tale 11. Hermit and Shajtan

Tale 12. Moses-pehambar goes to the god

Tale 13. Moses-pehambar talks to the god

Tale 14. Moses-pehambar becomes clear age of the God

Tale 15. Moses-pehambar and a girl

Tale 16. Moses-pehambar and shepherd

Tale 17. Justice of Muhammed-pehambar

Tale 18. Death of Moses-pehambar

Tale 19. The life is stronger than the death

Tale 20. Shere Ali pondered

Tale 21. Two brothers

Tale 22. Let us wait for a morning

Tale 23. The price of the palace

Tale 24. Kurdish heroic epos "Dimdim - goldenhand khan"

number 7:

MOSES-PEHAMBAR GIVES HIS ADVICE

Once Moses-pehambar saw that a shepherd was wheeling down from a hill. Moses-pahambar called the shepherd and asked him:

- Let God bless you, Kuro. Why are you wheeling down?

- I am praying the God, - answered the shepherd. Moses surprised.

- To pray the God you have to stay on your knees before God's face, but you have not wheel down from hill. And he stood down on his knees and showed to the shepherd how he have correctly pray and then left him.

Then Moses-pehambar approached to a sea and touched the water with his crook, and opened the road on the water before him. And he became walking on the water like on dry land. And the shepherd forgot everything and run after the Moses-pehambar and cried:

- Moses-pehambar, Moses-pehambar, please repeat me how I have to pray correctly?

Had a sight Moses-pehambar and see that his feet are little in water but shepherd's feet had none drop on it. And he said to the shepherd:

- Go away and pray as you can. I am Moses-pehambar but my feet are in water a little but yours have not a drop. You are holier then I am.

Moral from this lesson: no matter how to pray, the main to pray from the open heart.

number1:

DIMDIM - GOLDENHAND KHAN

They say, that in the times of shah Ismail, which was the governor of Iran, in a province Maraga lived one ajam - godless Ђsker-khan. In a province Xerari, boundary with Iran, there was a unassailable and very reinforces rock which called a Dimdim fortress. The prince, which holded it wore a name Abdal-khan. He was young and handsome, therefore he was named Goldenhand. The godless Asker-khan felt great hate to Abdal-khan and inhabitants of Dimdim. The godless Asker-khan gathered in Maraga an army in eleven thousand horsemen and infantrymen. He took guns, army and went to Dimdim to war with khan Abdal. He stayed near the Dimdim fortress and encircled it, that nobody could neither enter, nor to leave it.

In fortress Dimdim there was only seven hundred men, young and aged. Every day khan Abdal with one hundred soldiers attacked the enemy soldiers of Ђsker-khan and he came back with small losses - thus he led war with the Iranian army. The khan Abdal sent a message to pasha of Van about suege and has asked him for a help.

The army of Ђsker-khan enlarged daily. In a besieged fortress of khan Abdal the people died, and his forces rapidly decreased. Thus the army of Ђsker-khan, firing fortress from guns the Dimdim fortress during three months and repeating the attacks, reduces number of the warriors of Abdal-khan from seven hundred up to seventy the person. There was few ammunition and foodstuffs, many families and children died from hunger. The besieged have no place to wait for the help, they were not able to continue straggle with an enemy more longer.

So khan Abdal, not finding any exit out of the situation has called the council of the people, which one still have remained alive. "That shall we do, - he has asked, - what we shall undertake? Neither turks, nor Xekari, nor other Islam people till now have not sent the help to us; from seven hundred warriors, which we had, the majority was died in the battle; now we have only seventy the person alive, ammunition and the foodstuffs finished, the peoples are dying from hunger, so what shall we do? Do we have to surrender the fortress or to make the last attack?" Everybody on this council has said his opinion.

The mother of Abdal-khan, Goar-khanum, which also took part in the council, has exclaimed: "No! It is impossible to appeal for mercy and to surrender the fortress. It is impossible to believe to the words these kizilbashes, they will not keep their promises and agreements. Even if they will sign up the agreement, only in order to tear up it at once and to act with us as with enemies. We combated with such courage within three months, we have sacrificed so much soldiers, which one appeal to vengeance. Better we shall make the following: the men will open the gate of fortress, will leave it and will attack the enemy; we, the woman, who have forces to hold the weapon on the hand shall beat enemy near to you. That concerns to the girl and young wives, what couldn't to battle, let they will make a poison, and when all of you will die, they will drink it not to fall in the hands of godlessnesses. We will collect in one place all the last powder, and when the fortress will be filled by enemies, one of us will fire to it. We shall be blowed up, and the godlessnesses will die too".

Everybody approved opinion of Goar-khanum and have made the conforming alignment of forces. Each was ready to die. On Friday about midday khan Abdal with seventy men and twenty seven woman opened the gate of fortress and, saying goodbye one to another, with small and aged, with the wives and husbands, with battle call run out.

All girls and brides, which have remained inside, were accumulated by a poison and arose onto turrets to see a course of battle, and at this time wife of Abdal-khan, Asima-khanum, began to collect all powder and to pour it in a store-room below under the fortress and then pushed up on turret too to be see the battle. Then Abdal-khan has left the fortress with all his people, kizilbashes decided, that they are escaping, and they seized their sabres and have run to them. The khan Abdal and his daredevils have began bitter straggle at the foot of a fortress.

Last Dimdim heroes bravely shadowed against great number of godlessnesses. The women and girls, looked from the height of turret with the fool of attention, cried and prayed; children cried up to an exhaustion. Have died everybody up to the last person, but the losses kizilbashed were twice and even three times more. As soon as khan Abdal has died together with the soldiers and women, which one were with him in the battle, and then godlessnesses have run in the Dimdim fortress and their crowds have filled it. Many young wives and bride have taken in the poison. Asima-khanum fired a powder and blowed a part of a fortress with all the Persians in it; many families and children of Dimdim was died too, and there are very few people were salvaged.

The women and children who have stayed in alive, were then took out in servitude, the old men and elderly women was died, the fortress was burned. But the losses kizilbashes was incalculable. After that the Dimdim fortress has remained desert and empty. The place, where was the battle, is famous and sacred in Kurdistan, and Molla Bati Mim-Xey has composed a poem about this events. On the meetings kurds like to read it, they sigh, cry and say prays in the memory of Dimdim heroes.

Thunders, thunders, [listen to me],

All you, the nations of the world and all living on the ground!

[I] shall tell to you a story about Goldenhand khan.

Khano goes to Shah.

He asks:

"Present me land by the size of ox skin,

For I could build for myself a house on it".

"About Khano, do not demand it,

Do not build any Dimdim,

Do not cause us any disturbing!

Listen Khano! I can present to you a land by the size of ox skin.

For you could build for yourself a house on it,

But I am afraid, that you [could not] to complete [it].

Go, I give you patch of land by the size of ox skin,

Build to yourself on it a house ".

Khano was rose to his feet, and shah gave him chirek on credit,

Has built Khano the house - construction.

"[The shah] has gave me for the construction a place in five steps [length].

Inshallah, I'll build this house, that [even] khalif and shah will come to greet me".

You are wise man, Khano! You are clever man!

From ox skin has made duel,

Has fenced by it steppe and zozan - basically in mountainous areas;

It became a support for khans.

He softened ox skin,

Cut by it by razor, [that the belt became not thicker than a hair on head,

And covered by it the steppe and zozan. And he became to build the foundation of Dimdim,

Five hundred builders were occupied by it.

"Inshallah, Khano will have good health, then I could call bad lack".

[Here] he became to build Dimdim,

The holes made in rocks, filled by lead,

"Inshallah, I could call to you death".

When Dimdim have been built,

The holes made in rocks, were filled with a lead and cuprum.

"That have I do - the fortress's walls are narrow,

There are not enough of space for [laying] of rocks,

I have measured it by own hands, it makes three hundred eighty two steps widthway".

When Dimdim have been built,

Three hundred builders were beheaded, -

When main tower of a fortress have been built.

When the snow dropped out on the peak of mountain

And by the hoarfrost the steppe was covered,

Khano plundered a merchant's shah's caravan.

When turn white mining snow

And by hoarfrost the steppe was covered,

Hkano again began his brave actions.

The Mir Sejdo has gone to Shah

And began to complain him:

"All my army is erased,

In mountains against me have rebelled lions and tigers".

Shah answered: "Oh, a Mir Sejdo! [I do not know], is it true or not,

[But] Khan [to me] is the valid servant,

He never betrayed to me and progeny of my father".

[The Mir Sejdo answered:] "Of course, Khano [is] like this!

Khano is really raised by you,

[But] now he became an enemy of your faith".

[Shah said:] "Oh, son of mine. A Mir Sejdo! Mine courier has come for a long time ago,

And I know, that Khano has built the house by the size of beehive".

[Mir Sejdo answered:] "Oh, shah! Certainly, your courier has come already for a long time,

But not be deaf, blind and reckless, -

We by our own eyes saw, that on a wall of Dimdim were put a harness on twelve pair of the bulls.

Oh, yes, Khano [is really] like this!

Khano is really raised by you,

[But] now he became an enemy of your faith".

[Khano said:] " The misfortune has come on the lands of Kurdistan!

Collect gold, that it serve a payment,

We should build two water storages.

Bring to us the builders from [all sides of the] country, from [all it] cities,

For their labour pay by gold.

[Let] us will build a water line of twelve wells ".

[Shah ordered:] "Send a message Khalif

Also say him, [that] I give him the gold of Bamuchi,

[Let] he will go on the Dimdim fortress".

[Khalif said:] " Oh, shah! Let you give me two khans

Together with [their] horsemen and infantrymen,

I will destroy the Dimdim fortress".

What it was a day!

How much there was stars on the sky,

So much tents were stood up

Under The Dimdim fortress.

[Shah said:] "Oh, my mother! Oh, my mother!

Give me advice, [suggest] a solution,

Our life is finishing on this word".

[The mother said:] "Oh, son of mine! What is there? There - caravan of merchants.

They still should pay tribute to your father,

If they up to the morning will not pay, we with them shall fighting with them in battle.

Oh, son of mine! They are godlessnesses,

[They] have stood tents near us,

[And] the half of them have pack of a saddles for camels ".

Avdal-bek was young, he armed with a sabre and a shield,

Each night he went out from the fortress.

And three hundred Khalif's tents had made empty.

The commander became Avdal-bek!

He went out from the fortress,

Each night three hundred tents he had made empty.

[Khalif said:] " Send to the Sakh a message -

Let him collect army,

All my soldiers are dead,

In mountains against me have rebelled lions and tigers.

Say to Shah, let him come,

But let him not to make mistakes,

In the fortress against me has rebelled the tiger".

The winter passed, the spring has comes to us,

It is necessary to arm the army,

The kurd's khan is in enmity for us.

The spring passed, the summer comes to us,

It is necessary to collect army,

The kurd's khan - against us.

The summer passed, the autumn come to us,

The armies have good weapons,

The kurd's khan is angry with us.

The autumn passed, the winter comes to us,

Lift the large army!

We will have a campaign against kurd's khan.

One khan is on the way, he approaches closer and closer,

His rear guard for is near the Saline sea,

And advance-guard - [already] near of walls of a fortress,

One khan goes from Salamast -

Somebody tells, what is it lie, and somebody - that it is truth.

Inshallah, will be a khan alive and able-bodied - the blood will stream like acidic milk.

One khan arrived from Taures,

Behind of him stood up the horses in line, [loaded by guns];

"Inshallah, fortress Dimdim I shall destroy by battering-ram".

One khan goes here from Kinjuminje, he nether the Armenian nor kurd:

"Inshallah, Dimdim fortress I shall make a target [for my guns]".

One khan goes from Eruvel, [It seems], all world he collected, going against fortress:

"Inshallah, hardly khan could remain alive, I swear by my own whiskers".

When the khans have collected together,

There were all of them thirty two,

Near Dimdim they have stood, [Shah said:]

"Oh, Khano! You are kurmange,

Accept this crown, [instead of that]

We will make you a target for my guns".

[The Khan answered:]

"I shall not accept your crown.

Seven times I damn your father!

I will not disgrace kurmanges".

[Shah said:]

"Now matter has came to guns,

Shoot from guns on the khan's fortress!

Destroy the khan's fortress!"

Dimdim - is a ridge rock:

There are muskets and guns firing on it,

Watering like a rain -

The rain of bullets is watering on the fortress.

Dimdim is - round rock:

They go on it with picks and axes,

Cloud of a dust closed the sky.

Dimdim is - rock in water:

Five hundred gun salvos shoot at it -

None stone have been moved from it place.

[Shah ordered:] "Bring up large guns,

Win expensive necklaces and rings,

Fire at Large fortress turret,

Destroy the fortress of khan up to the foundation!

Bring up small guns,

Win expensive necklaces and mirrors,

Fire at Market fortress turret.

Bring up Long-range guns,

Lying along of wagons.

Fire at a fortress of khan!

Destroy a fortress of khans!

Bring lengthy guns,

Charged by gunners for a long time ago,

Shoot at rooms, where they are praying.

Bring guns from Barzan,

Which muzzles are bowl size,

Fire by them at turrets of khan.

Bring here guns from Enzal,

Which muzzles are about the boiler size,

Fire by them at fortress turrets.

Gunners, prepare the guns!

Make hundred gun fire volleys,

Destroy the Dimdim fortress".

Gunners prepared their guns,

Hundred guns fired together,

[Then] they have been charged again,

Have fired at fortress walls, -

[But] none rock have been moved from the place.

Be damned a kind these gunners!

[Like] by blank charges they have shot -

And a stone they have not moved from it's place;

"Gunners! Bring up guns,

Put in larger powder,

Input two cores in each gun,

[For] the cores would adhere to the walls of the fortress, -

Fortress Dimdim become rickety"

Gunners brought up guns,

Filled more to powder in it,

Have charged with two cores each gun,

Have directed them on walls of the fortress -

Fortress Dimdim vibrated.

The large guns rumbled -

The large turret thundered out,

Lions on it is loudly howled.

The large guns fired -

The large turret buzzed,

Lions cried out their names.

"Bring guns with golden muzzles,

Which cores have weight in hundred vakin".

The khans were sleeping [in Large turret],

[And] they have not known about guns.

"Bring guns with black muzzles,

Which cores have water-melon size,

Destroy fortress of the khan,

[Let] the Large guns shoot,

Erase the part of turret.

Then khamunes will cry".

The large guns have shot,

And the part of turret was destroyed,

Khanumes have begun to cry,

"I khan, Goldenhand khan,

The fortress Dimdim is made from rock -

There is not a crack in it,

Thanks God, I was not Dimdim, [and] became Dimdim,

I was kurmange, [and] became khakim,

Now shah of agames has come to destroy the fortress.

When my heart cries,

To the sky are flying the birds of my fortune,

Seven years we growing the garden and [already] are eating the grapes from it".

As soon as passed seven years,

The dog of the Knan has brought puppies,

[Then from its milk] have cooked acidic milk and have sent to shah.

Shah said: "Already passed seven years,

Acidic milk we could not find anywhere,

And [suddenly] this food bring to me from the fortress?..."

He ordered: "We shall hurry! Let's hurry!

Saddle horses!

Otherwise we shall be erased by kurdish khans".

[And here in the fortress] has appeared damned Mahmad,

[He] has winded the letter around of a arrow

And has send it in a shah's tent,

He informed on a place of a spring and underground water line.

And appeared Mahmad, [the son] bagy,

The letter on leaf of pear-tree

Indicated a source of a underground water line,

Appeared Mahmad Alakani,

Ulcer to you under your tongue! -

He became the reason [ of destruction] of Khan's stability,

He linked in chain little rings,

Mahmad on it was dropped downwards [from the fortress].

[Shah said:] "Bring him, I shall interrogate him".

Mahmad said to the servants [of shah]:

"If it is not a shame [for shah],

I would like become [him] a servant".

Shah said: "Oh, Mahmad Alkani!

You are dog, [you are] - devil's kin,

Why you became the betrayer of Temir-khan?"

[Mahmad answered:] "Oh shah, it was like this and not like this,

Each day he presented to me a shield, [full] of gold,

And today has not make me present,

Therefore [and] I betrayed him".

[Shah said:] "Oh, Mahmad Alkani!

You are dog, [you are] - devil's kin!

I have got here three hundred foreign servants,

I [even] not each day I give them a piece of bread,

If they will betrayal to me, my bread will kill them.

Bring, bring, bring,

Large gun here bring!

Input in it Mahmad,

Flatten out him into the fortress's wall!"

"We have brought, we have brought it!

Large gun we brought here,

Have input in it Mahmad,

And flattened him into fortress's wall ".

[Shah] said: "Let hell take you, Mahmad Alkani!

You are dog, [you are] - devil's kin!

You wanted serve to me, like to Temir-khan?"

Early in the morning sent kafires their leaders,

[And] they saw the source of water line.

Early in the morning, when faki have undertaken for msines,

The water in waterstorage has appeared blended with a blood.

Khano examined the water line, -

As like fire burned his heart:

"Oh, my god! It is sick to me for children in cradles".

When they were cut from the water line,

The teardrops did not stop on eyes of the khan:

"Oh my god! It is sick to me for children in swing cradles!"

The Khan called the council,

[He said:] "The life is sweet, the sin - is high-gravity.

Who wants to leave with family, let go, [I] give him my permission.

Who cares about his goods and about children,

He should not go with me,

Let there not will be sin on me before the god".

They answered: "Oh, Khano! The khan-leader".

Faki armed with bows and arrows:

"We shall lose our heads only on the tomb of our Khan-leader".

[The khan said:] "Oh, my mother! Oh, my mother! Give me advice and suggest me the solution,

Our life comes to end on this word,

Nobody will come to help us".

[The mother said:] "Oh, my son! Be afraid of the god!

Give to noble horses enough forage!

Which of you will leave house with sword in his hand?"

[Hahn] said: " Hurry, hurry!

Break out doors of treasuries,

Melt our gold and silver!

Dip there sabres our man -

Who will own them after our death? "

"We have hurried, we have hurried,

We have broken out doors of our treasuries,

We melt gold and silver,

Have dipped there sabres man".

"Go on the upper floor,

Wake newlyweds behind canopy -

[Is it possible] for father should wait for his son!"

Avdal-bek stood up, stood up,

He an put on armour from the skin,

The squad of the young men has gone behind him,

Near the father he stood up,

In one line with his father he stood up,

[And] even exceeded him a little.

Avdal-bek said to his wife:

"Oh, you, small, with a bracelet on your arm,

Shah gave your to me in the wife,

How much young men were ruined by it".

[Khan said:] "Hey, lead here the young man from sharaf;

You on battle field do not swear [for nothing],

Take better double-edged sword.

Lead here the young man from banana -

Brave man of our time;

Take damask-xorasan sword.

Lead here the young man from dershive;

On the battle field you must hope only on yourself,

Take sword with silver ephesus.

Call the young man from mall -

He among weapons of the Khan

Have chosen to itself [only] this truncheon.

Call the young man from bilbases;

On battle field you are brave man,

Take here this musket. Oh, young man from bektar,

You live in inaccessible mountains.

Come, select [to yourself the most] best weapon".

"The word the man is strong,

If I shall take a sword and he will break in my hand,

And it will be a shame to me before you.

Khano, I ask you,

Make one sworn from two ones,

Make a steel shield,

Dress on it a bronze hoop,

Then I will no feel fear before shah's army".

Khano stood up, and rapidly run,

The Khan has come running to the blacksmith,

"Oh, blacksmith! Let me ask you,

Make one sword from two ones,

Make a steel shield,

Encircle it with bronze hoop,

[For] with this [weapon] it would be possible up to reach to shah's tent".

The blacksmith rose and rapidly run,

Has made steel shield,

Encircled it with bronze hoop,

Gave it to kurd's khan.

The Khan came backward,

He said: "Oh, my son! Take your sword,

Defend by it".

The son took the sword,

He cried out the name of god.

Once waved by sword -

The sword's hand lever has flown away.

Be are damned the fathers of these blacksmiths -

Their work [anybody] it is not necessary!

[Let] beards of their fathers be in manure,

Who such sword [is necessary]?

It need throw it on the tomb of the blacksmith's father".

The blacksmith rose and quickly run,

Took Khano's sword,

Riveted it by two nails,

Returned sword to khan Mukri,

And said: "Now go on a field of swearing and do not complain of us ".

Khan has come back backward,

And said: "Oh, my son! Take the sword,

Defend by it".

The son took the sword,

Cried out the name of the god,

Once waved by sword -

Sword was came as desirable.

[Khan] said: " Rise! Rise! Let us go!

Let's saturate sword with blood! Better mores, than such life. Rise!

The time favours us,

Release belts of shields,

We from the god wait for success and good luck ".

Rise! It is time. It is time to release belts of weapons,

We from the god wait for success and good luck ",

Avdal-bek has gone away from a fortress,

To a new source went,

He drank water from a spring,

On a rock leaned his elbow,

Long glass to eyes he affixed,

Tents of kafirs he counted -

There are forty thousand ones, no one there are less.

"Oh, father! Count tents of kafires,

There are no less them than forty of thousand:

With black banners, -

There wings are open,

They are cut to us roads and [mountain] passings.

With yellow banners, -

It is the soldiers [from armed] of squads,

They cut to us approaches to forts and bridges.

That with red banners, -

It is the soldiers, [having] by huge force,

They enclosed us.

That with white banners, -

It is the people with sabres,

They cut to us from the source of water.

That with parti-coloured banners, -

This is the people noble and famous,

They already have occupied a part of battle field,

With blue banners, -

It is the people from Bakdian,

They are by force leaded here,

[And] I have no fear before them.

Ah, my father! You lingered a long time,

[We] want to attack with swords this concourse.

Oh, father! Let us stop waiting in disgraceful calmness,

[We] want to attack with swords an enemy,

Will not come more help from kurmanges.

Rise! Rise! Be ready!

Clean Khano's horse,

Dress on a gold bridle,

Give your life for my father".

Dressed [gold] a bridle,

Have tightened belly-bands of Khano's horse.

Up to thousand [of the soldiers] they had.

[The tartar-bek cried:]

"I the nephew of khans,

[I] am chained and I am tied,

There are not me in your lines".

"Yes, you are the nephew these [strong] elephants,

Tear the hobbles and fetters,

Hurry to the aid of the khan of the emirs!"

The tartar-bek shook yourself,

Hobbles and fetters has torn,

Of tent jumped out,

To the aid of rose.

Beet trommels, play nikares!

- Them became one thousand.

Goldenhand khan-sadar [said:]

" I am Khan from the khans-emirs,

My head - [as] a anvil before arrows,

My chest - [as] a shield before swords"!

Stood up a khan with gold fingers,

By belts he tied himself:

"I lead struggle - [ my struggle is] true".

[They] came to hard-to-reach gates.

[Khan] said:

"We will go on foot,

I hope - we shall stay alive".

They came to a stair,

Growled against each other two lions,

One on a name of Kar, other on a name Kanun.

"I am khan - Godenhand khan,

The master of the Blue sea,

I will disgrace you".

"I am khan Avdal from Botan,

I shall pass the sea on a floor,

I know, what shame on you".

"Tomorrow army will be dissolved.

Without forages, without bread and waterless,

Wake up early, as soon as I give the sign to you".

They dropped up to the upper door,

Khan growled, like lion.

Sent khalif the Hahn a crown -

Khalif acted slyly.

"Oh, khalif, you are aged dog, you are running behind bitch,

The dog's manure in your whiskers

I do not admit your crown,

In the name of god and the prophet I do not admit your crown,

Eight hundred damnations to your father,

Kurmanges I not shame".

[Khalif said:] "Oh, Khano! Many problems it is not a sin,

Whose visitor would you be today? " [Khano said:]

" We are the brave men from Dimdim,

The we are masters of our swords,

We hesitate [to be the guests] of shah,

We [better] we shall the khalif's guests;

We - brave men from Dimdim, dancing [in the battle],

We are owners of swords with diamonds,

We - shah Abbas's guests".

[Khalif said:] " Oh, Khano! Here are countless set of visitors,

In whose house do you want to be a guest this night?

You are for me desired guest,

Take off your weapon,

Lean your elbows on pillow! "

Khano set down with weapons,

Khalif surrounded him with pillows, -

He did this way for to kill Khano.

Khano sworn on the sacred book:

"Weapons I shall not take off

Up to evening council".

Decided Khano in a tent

To take out sword from scabbard

[And] has not delayed it in it.

"Cut on kafir's necks!"

Khano cried out in the name of god,

He put out sword from scabbard,

One sweep -

Cut off a khalif's head and his nephew's ones.

The noise - was awake up in the army

Panther are let out on wild boars;

Khalif and his nephews are dead.

"Get up, Avdal-bek, -

You are in mail;

We have killed many men".

Avdal-bek in fight has turned back,

He put out sword from scabbard, [holds it] in hands.

The Khan tells to the son:

"Well, open the wings,